I spent this past May reading and browsing the archive of The British Newspaper Archive. In collaboration with The British Library, this platform provides access to the largest online collection of British and Irish historical newspapers. The archive also contains some Canadian newspapers.

“Million bags of flour from Canada”

You can imagine my surprise when I came across a collection of English and Irish articles in August 1914 with the headline: “MILLION BAGS OF FLOUR FROM CANADA”.

A million bags of flour from Canada?!

The newspapers reported on the Canadian government’s donation to the people of the United Kingdom during the first weeks of the war.

“The Board of Trade announces that the following telegraph communicatons have passed between the Duke of Connaught, Governor-General of Canada, and the Secretary for the Colonies: “I am desired by my Government to inform you that the people of Canada, through their Government desire to offer one million bags of flour of ninety-eight pounds each as a gift to the people of the United Kingdom, to be placed at the disposal of His Majesty’s Government, and to be used for such purposes as they may deem expedient. This size is most convenient for transportation. The first shipment will be sent in about ten days, and the balance as soon as possible afterwards. – ARTHUR.”

Received 6.40 A.M., 7th August.

Reply sent:

-“12.45 P.M. 7th August.

Your telegram, 6th August. His Majesty’s Government accept on behalf of the people of the United Kingdom with deep gratitude the splendid and welcome gift of flour from Canada, which will be of the greatest use in this country for the steadying of prices and the relief of distress. We can never forget the promptitude and generosity of this gift and the patriotism from which it springs. – HARCOURT”[i]

The first bags of flour were readied in the Canadian mills on August 20th. On September 9th, 1914, 50,000 bags of flour had already arrived in Liverpool. Each bag was printed in color with large letters “FLOUR. CANADA’S GIFTʼ.

The background of the impressive donation turned out to be considerations of financial nature. “In the work of financing the exports of grain and flour from Canada, the arrangement completed by the Bank of England, under which the Canadian Minister of Finance has become the depository of important gold reserves which otherwise would have been shipped across to England, is of high importance, as the large sums paid into the Treasury at the Canadian capital can be paid out to exporters of produce from the Dominion. The effect of this will be to relieve the financial tension considerably.” [ii]

Another message explained, in my words, the dual purpose of controlling bread prices and the ability to come to the aid of the poor.

“What use is to be made of Canada’s Gift is under the consideration of the Government, but it is thought it will be used for the dual purpose of easing the market and relieving distress.”[iii]

The bags of flour were mainly stored in the ports of London and Liverpool.

But the ports of Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Dublin and Belfast also had flour from the Canadian donation in storage. The Port Authorities had undertaken to warehouse the gift of flour as long as necessary without charge. The Food supply management was entrusted to the Local Government Board, which was to establish a method for distributing flour to the population; it turned out to be an issue that had not yet been decided. The total value of the donation was estimated at half a million pounds sterling.

Film footage of the unloading of bags of flour in the British port of Cardiff has been preserved in the historical Reuters collection and is available online at “British Pathé”. The steamship Riversdale from Sunderland came from Montreal, Canada, and docked in Cardiff in October 1914. The title of the 30-seconds film clip is “Ireland’s share in Canada’s Gift of Flour.”

“Canada’s magnificent gift to this country of 1,000,000 bags of flour will come in the main to London and Liverpool. Its care will be taken over by the Relief Committee of the Local Government Board and the Regulation of Food Prices Committee of the Board of Trade. At present no decision has been reached as to the exact method by which the gift is to be utilized. The approximate value of the flour at wholesale prices is £ 500,000. The Port of London Authority and the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board have undertaken to warehouse it as long as necessary without charge.”[iv]

Donations from the Canadian provinces

Canada provided more gifts. The Canadian provinces donated food and fuel. Alberta donated 500,000 bushels of oats, Quebec, the French-speaking province, 4,000,000 lbs of locally made cheese. Nova Scotia donated 100,000 tons of coal. British Columbia contributed with 25,000 cases of canned salmon and New Brunswick 100,000 bushels of potatoes. Ontario’s gift was £ 100,000 to be spent with them by the British government as needed.[v]

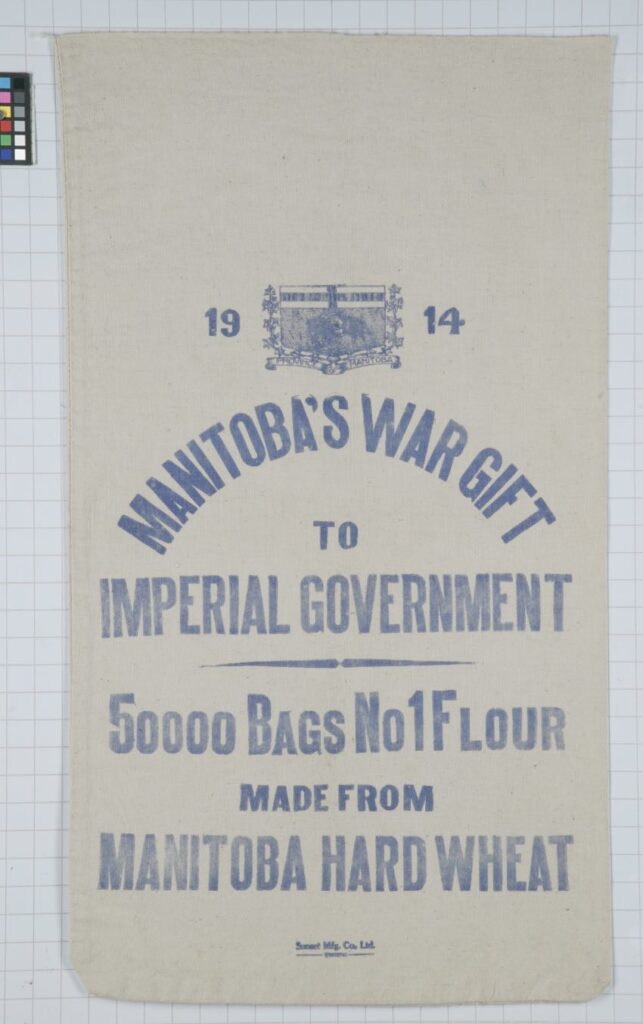

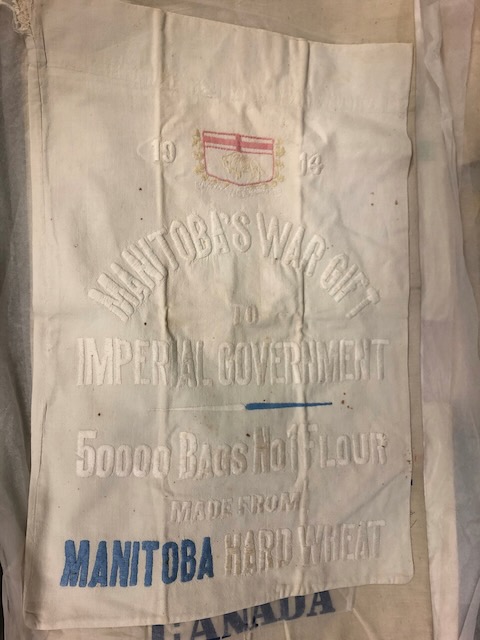

Manitoba’s Gift

The province of Manitoba donated flour to the Motherland: “MANITOBA’S GIFT. The War Press Bureau announce that the Colonial Office has accepted an offer of flour from Manitoba.“[vi]

“The Government of Manitoba has awarded the contracts for its gift of flour to all the principal mills at a cost of 2 dollars 90 cents and lower. The flour is the finest the province produces and will be rigidly inspected. It will be ready by October 20th. – Press Association War Special”[vii]

“Bags are sold for 5 shillings each”

My surprise at the one million bags of flour from Canada increased as I read a letter from a housewife in Dundee, Scotland. Immediately after the first report of the donation of one million bags of flour to the United Kingdom, she had an idea for the use of the empty flour bags. She wrote a letter to the local newspaper on August 25th.

“Every housewife knows what a great many useful things can be made out of flour bags, and one of the gift bags would be a lasting souvenir of this great war…” DUNDEE HOUSEWIFE

August 25, 1914”[viii]

The suggestion has to have been embraced with enthusiasm and broad support, because from mid-September on, the newspapers published a stream of calls to subscribe to the sale of flour bags. The proceeds went to charity.

‘CANADA’S GIFT

Sacks to be Sold at 5/- Each.

Canada is making a splendid gift of flour to the Mother Country. It has been decided that the sacks, when empty, shall be sold as souvenirs at 5s. each. Two-thirds of this sum will be devoted to the Prince of Wales’ National Relief Fund (N.R.F.) and one-third to the Belgian Refugees Fund (B.R.F.). The sacks are all marked ‘Canada’s Gift.’

Applications for the sacks as souvenirs, accompanied by a remittance of 5s. should be sent to the National Relief Fund. Applications will be dealt with in strict rotation.‘[ix]

Next an informative article appeared about the sale of the empty flour sacks. Its headline was “CANADA’S GIFT SACKS. HOW TO BUY THEM AND HOW TO USE THEM.“[x]

For interested parties, 10,000 empty flour sacks became available starting December 9th, 1914. The specification of the sacks was as follows: 98 lbs sacks, made of gray calico (sturdy fabric of unbleached cotton). Dimensions were 36 inches high and 18 inches wide, or cut open, 36 inches wide. One side of the sack read in colored large print letters “FLOUR. CANADA’S GIFT.”

Lovers of the flour bags made suggestions for use. The material could be embroidered and cushion covers could be made. In particular, it was mentioned that Red Cross hospitals could use it to make their cushion covers, and even mattress covers for cots. Some wanted to hang a flour sack at their political club, another club or in schools. The suggestion was to make a copy available to all museums. With the approaching Christmas season, the idea arose to designate the bags as “Christmas gift bags”. And a very ingenious housewife planned to cut up her flour sack to prepare her Christmas puddings.

In December, a Canadian newspaper concluded with the headline “Selling the Sacks. How Canada Achieved a Double Purpose.”: “Thus, Canada has benefited the Motherland two-fold by her generous contribution. Not only has she helped to feed England, but she has also, by this gift, helped to swell those two very deserving funds (the National Relief Fund and the Belgian Relief Fund) now so prominently before the public.”[xi]

Marking

Ultimately, only 1,500 bags of the 10,000 bags made available were sold for charity in England. (La métropole d’Anvers paraissant provision à Londres, January 21, 1915)

On December 26th, 1914, the shipment of empty flour bags to the buyers had started. The marking of each bag was: “N.R.F., B.R.F., 1914” as proof that the proceeds from the sale were destined for the National Relief Fund and the Belgian Relief Fund.[xii]

Sheffield

Within a month, two photos of a decorated Canadian flour sack appeared in Sheffield newspapers. The canvas bears the stamp “NRF, BRF, 1914”. A lady from Sheffield made the cushion.[xiii]

The first picture showed a flour sack transformed into a cushion. The pen drawing shows a bulldog – symbolizing Great-Britain-, in the dog’s mouth the British flag. The dog is sitting on a piece of paper, next to it is written “Scrap of Paper”.

“Scrap of Paper”

The drawing refers to the Treaty of London of 1839, the definitive international recognition of Belgian independence and the establishment of the borders between Belgium and the Netherlands. The United Kingdom, France, Austria, Prussia and Russia signed the treaty, guaranteeing the neutrality and security of Belgium.

When the Germans invaded Belgium on August 4, 1914, violating its neutrality, the British stood by their guarantee and declared war on the German Empire. The British ambassador had informed the German chancellor that the UK would declare war on Germany in the event of a breach of Belgium’s neutrality. The Chancellor responded that he couldn’t believe the UK would declare war because of “un chiffon de papier” (“a scrap of paper”).

Indeed, other arguments were decisive: for example, the British did not want the German navy to take possession of the Belgian seaports.

The second photo showed a pillow that read “FLOUR. CANADAʼS GIFT.” It was also decorated with a pen drawing, now with flowers.[xiv]

Both photos may have been of one and the same cushion, front and back, respectively. The same corded edge and the two tassels on the corners would suggest this to be the case.

January 25th, 1915 an auction was held for the benefit of the Belgian Refugees Fund during the Bohemian Concert at the Royal Victoria Hotel. The decorated flour sack was to be sold there and the proceeds benefited the local Belgian refugees.

Canada’s Gift to Belgium: More Sack Souvenirs

The British newspapers provided me with a third surprise.

I kept reading the Sheffield newspapers and saw an article about aid from Canada for the Belgian refugees in England.

“Canada’s Gift for Belgians.

Sheffield’s share of the gift of flour, potatoes, and cheese which Canada has sent for the Belgian refugees who have settled in England, is being distributed to the various areas and bases at which the refugees are residing, and will from these different centres be divided among the individual recipients.”[xv]

Immediately afterwards, empty Canadian flour sacks were once again in the spotlight, in particular the specimens that had been donated filled with flour to the Belgian refugees.

“The sacks containing the flour sent by Canada as a gift to the Belgians are attracting considerable notice, and like those which contained the Dominion’s gift to England, are being sold as souvenirs. The colours used on the bags are those of Belgium – red, yellow and black -and the words printed thereon are “To the Belgian people, God bless them. Canada’s gift.” In years to come these will not be readily parted with.”[xvi]

Canadian flour sacks decorated in Great Britain

Hardly recovered from my surprise, I draw a remarkable conclusion from all these newspaper reports: Canadian flour sacks in the skilled hands of enthusiasts in Great Britain will have provided the example and inspiration for selling empty flour sacks and decorating the sacks in Belgium. Through the charity and work for Belgian refugees, ideas must have crossed the Channel well before any food aid reached occupied Belgium.

Addition 3 June 2023

Another surprise on June 3, 2022 during my American Sack Trip. In the C.R.B. archives of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, I find evidence that the C.R.B. headquarters in London bought 20,000 tons of flour from the British in early December 1914. Indeed, that was the Canadian flour that would not be used by the British for the time being…

You can read it in the blog Meelzakken met Belgische dank aan het ‘Moederland’. (Blog in Dutch, use orange Translate» button for translation in English)

Canadian Flour Bags/ Sacs Canadiens

Canadian flour bags/<<sacs canadiens>>, 1914-1916. Photos and collage Annelien van Kempen, 2025

Canadian flour bags/<<sacs canadiens>>, 1914-1916. Photos and collage Annelien van Kempen, 2025

Table of contents: blogs on the Canadian flour sacks:

Canadian flour sacks and the thoroughly exaggerated “Tribute to America”

Lake of the Woods Milling Company, Keewatin, Kenora, Canada

Canadese bloemzakken met Belgische dank aan het ‘Moederland’

Dank van Puers/Flour Canada’s Gift

Thanks to:

– the Lizerne Trench Art Facebook group, especially Jan Derynck, Ivan Ryckx and Maarten Bondam, for their information and thoughts on the symbolism of the drawing on the Sheffield flour sack “Flour Canada’s Gift, Bulldog on “Scrap of Paper”” (January 2023).

– Joanna Dermenjian for newspaper articles and flour sack finds in Canadian collections. Joanna is researching Canadian Quilt History, Canada’s Wartime Quilts – 1939-1945. Her website: Suture and Selvedge

[i] The Scotsman, Augustus 10th, 1914, South Wales Gazette, August 14th, 1914

[ii] Newcastle Journal, September 9th, 1914

[iii] Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, September 9th, 1914

[iv] Millom Gazette, September 11th, 1914

[v] The Cornish Telegraph, September 3th, 1914

[vi] Western Chronicle, September 11th, 1914

[vii] Sheffield Evening Telegraph, October 6th, 1914

[viii] The Courier, August 28th, 1914

[ix] Sheffield Evening Telegraph, September 24th, 1914

[x] Evening Despatch, October 31st, 1914

The article has been published in many newspapers.

The Canadian newspaper St. Catharines Standard, Ontario, wrote on January 7, 1915: “Canada’s Gift Sacks. How the People of Britain are Buying and Using Them.” They clipped it from the columns of the Courier, of Inverness, Scotland. (thanks Joanna Dermenjian!)

[xi] Whitby Gazette, December 18th, 1914

[xii] Chester Chronicle, December 26th, 1914

[xiii] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, January 23rd, 1915

[xiv] The Sheffield Daily Independent, January 23rd, 1915

[xv] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, January 11th, 1915

[xvi] Todmorden Advertiser and Hebden Bridge Newsletter, January 15th, 1915