To me, the WWI decorated flour sacks of the Madame Vandervelde Fund stand out. It makes me happy to know that there was a woman who came to the rescue of the Belgian people with conviction. That woman was Lalla Vandervelde-Speyer (Camberwell, England, April 4, 1870 – Putney, England, November 8, 1965). She is one of the many women who worked determinedly towards her goal: care for destitute Belgian compatriots. Her decorated flour sacks also tell the story of charity, gratitude and food aid.

This is part 1 of a series of three blogs.

(See my blogs: Madame Vandervelde Fund 2 and Madame Vandervelde Fund 3)

Charlotte Helen Frederica Maria Speyer was British-born, from an affluent Jewish family. Her parents were German by birth and settled in England after their marriage in 1869, where father Edward Antoine Speyer had previously joined his older brother Carl in 1859 in a very successful haberdashery importing business. Lalla came to Brussels as a 16-year-old teenager to continue her education.

She married Belgian mining engineer Hubert François Edouard Ferdinand (Ferdinand) Kufferath (ºSaint-Josse-ten-Noode 1855.07.28 – †Schaerbeek, 1920.07.14) in Reigate, Surrey, UK, on 19 January 1892 and would continue to live in Belgium. The couple divorced officially on January 3, 1901.

Lalla Speyer’Kufferath’ remarried on 15 February 1901 in Fulham, London, to the Belgian socialist politician Emile Vandervelde (ºElsene 1866.01.25 – †Brussels 1938.12.27).

In Brussels 1914

When war broke out in August 1914 and Germany occupied Belgium, Lalla Vandervelde was forced to leave her new homeland, together with her husband who was appointed Minister of State.

Lalla was 44 years old and in the prime of her life. Her name, Madame Emile Vandervelde, -this was the Minister of State, who was her husband- appeared in ‘L’Œuvre des femmes bruxelloises’ as one of the presidents, next to ladies Henry Carton de Wiart and Paul Hymans, to whom Queen Elizabeth requested that they take care of children of military personnel who went to battle with the army. The vice-presidents were Messrs. Brassine, Leroy, Prosper, Poullet, Paul Vandervelde and Philippson-Wiener. The Queen was the patroness of the organization.[1]

Lalla’s work experience for the socialist movement, her women’s suffrage activities and her completely autonomous nature led to immediate decisive action in the crisis situation of the first weeks of the war.

She published this advice in the newspaper Le Soir to women who wanted to make themselves useful.[2]

“For those who want to help

An excellent letter from Ms. Vandervelde:

Many women and girls have been writing to me for the past few days asking for advice on how to be helpful in these scary days. The ambulances are full of women of goodwill, but there are many who are just waiting to be of service to their country. I would like, as it is impossible for me to answer each of them individually, advise them to sew a lot of men’s shirts, children’s dresses, knit socks, etc.

The blue smocks of civic guards, too, which are urgently needed, are cut out, all ready to be sewn, 3 Rue de Louvain, at one of the ministry’s offices. By going there on my part, they will gladly give it to all those who request it.

Let friends’ groups form: let one of them take a book and read it to their friends. Not light reading. We are in a phase of heroism and women, mothers and expectant mothers must not let their emotions take over. By their calm and cold blood, they can do precious services right now. What to read? The History of France by Michelet; The History of Belgium, of Pirenne; The Legend of the Centuries, The Turbulent Forces, by Emile Verhaeren, etc. I note these few titles in a hurry, but in each one you will find beautiful pages which have already allowed them to endure the consequences of existence.

Lalla VANDERVELDE

P.S. – I beg the merchants of cigars and cigarettes and the individuals of good will to send me something to smoke for our soldiers, soldiers and wounded. If they could get an idea of the joy of our brave people when they are given something to smoke, I am sure that my house would be too small to contain everything that would be sent to me.”

To America

Lalla Vandervelde was still in Brussels when she wrote the quoted advice. Two weeks later she had to leave to stay out of the hands of the advancing German troops and she moved to Antwerp. On the spot, the plan arose to travel to America to ask for help from the women there. On September 1, 1914, she sent a telegram to New York calling on American women to come to the aid of the Belgian people.

The New York Times posted the “Appeal” in the Sept. 2 edition on p. 3 under the heading:

“SENDS AN APPEAL TO AMERICAN WOMEN

Mme. Vandervelde Coming Here to Tell of Belgian War Victims’ Sufferings.

HAS LETTER FROM QUEEN

Wife of Socialist Leader Will Sail for New York in a Few Days- Says the Need is Terrible.”

The article read:

“LONDON, Sept. 1.-Mme Vandervelde, the brilliant wife of the famous Socialist leader who is now Minister of State in the Belgian Government of National Defense, sends the following appeal to the women of America through the columns of The New York Times:

Women and Friends in America: I am coming to ask your sympathy on behalf of my fellow-countrymen in Belgium. It is not a political mission. It is an appeal for help for devastated homes, the fatherless families of those whom this terrible war has left houseless, who, when the war is over, will be left without rooftrees, without money to rebuild them, and-and all too often-without sons or husbands to work for them.

I am the bearer of a letter from our well-loved Queen. I only ask you to give me an opportunity of reading it to you and telling you in person of our tragic conditions and of asking your help. I am leaving Antwerp only for this purpose, and as soon as I have accomplished it am returning to share the fate of my countrymen in our besieged city.

…….

That is why, women of America, I am coming to you, leaving for a few weeks the country for which my heart is bleeding. I want you, I count on you, to make life worth living again for these poor people, make them by degrees forget the sorrows they have passed through.

Belgium is ruined. You are enjoying all the blessings of peace. I implore you to help my country, to make it by your generosity once more a happy home for its sons and daughters.

LALLA VANDERVELDE

Mme Vandervelde purposes to sail for New York in a few days, by which time she hopes to hear that the American women to whom she appeals have taken steps to obtain for her a hearing when she arrives.”

In Londen

Lalla Vandervelde travelled to America via London, together with “La Mission Belge aux Etats-Unis”, the Belgian mission of four ministers, who had been ordered by King Albert to explain the Belgian position on the condemnable and brutal invasion of the Germans to US President Wilson. One of the ministers was her husband Emile Vandervelde.

“The Belgian Mission in the United States.

The Belgian mission to the President of the United States arrived in London Monday evening, and before his departure from this city, set for the following day, was received by the King of England at Buckingham Palace.

….

Mr. Vandervelde is accompanied by Mrs. Vandervelde, who will give lectures to women, in the cities of the United States.”[3]

Lalla and her husband assumed she could make the trip to the US on the same ship as the official Belgian delegation, but this was a miscalculation. They were formally told that: “no women ever had, or could, in any circumstances, accompany a diplomatic mission”.[4]

That they were not the only ones who had expected otherwise is evident from the rectification, “because of transmission and translation” in La Métropole of September 5, 1914:

“Correcting our comments, we add that it is also incorrect that Madame Vandervelde will accompany her husband during his mission to the United States.”

The words “also incorrect” referred to an earlier newspaper report that Lalla Vandervelde was going to make the journey with a letter from Queen Elizabeth.

No, the letter was not from the “head of the court of H.M. the Queen”, but “This is a letter written by a lady from the Queen’s service to the wife of our new Minister of State, in response to her offer to make known in England, during a series of conferences, the situation in Belgium.”

It made me curious about the contents of the letter from Queen Elizabeth’s court, which Madame Vandervelde had read at the Eighty Club at the Cecil Hotel in London. Curiously, that letter left nothing to be desired for positivity and clarity:

“Sa Majesté la Reine me prie de vous dire qu’elle approuve pleinement votre intention de porter à la connaissance de l’opinion publique en Angleterre et en Amérique, les misères infligées à notre paisible population, par l’invasion allemande. Cinq de nos provinces sont dévastés, des milliers de famille chassées de leur demeure et actuellement sans domicile, et c’est une œuvre qui mérite la reconnaissance du pays et de l’humanité, que de chercher à les secourir. Les meilleurs souhaits de la Reine vous accompagnent dans ces deux pays, qui auront à coeur de donner assistance à ceux en détresse”.

(“Her Majesty the Queen has asked me to tell you that she fully approves of your intention to bring to the attention of public opinion in England and America the miseries inflicted on our peaceful people by the German invasion. Five of our provinces are devastated, thousands of families driven from their homes and currently homeless, and it is a work that deserves the recognition of the country and of humanity, to seek to rescue them. The Queen’s best wishes are with you in these two countries, which would be keen to give assistance to those in distress”.)

Was this a way for some gentlemen on the side of the Belgian government to show a woman, in particular a representative of the socialist movement, her place at the start of the mission to America? Was it protecting women against their desire for autonomy? In any case, it took patience and resilience to walk the line, even under war conditions…

Travelling

Lalla Vandervelde was in no way restrained. She traveled to New York, where “The Belgian Women’s Dollar Fund” was founded the day her “Appeal” was published in the New York Times. ‘It received its first subscriptions before noon of the same day’.[5]

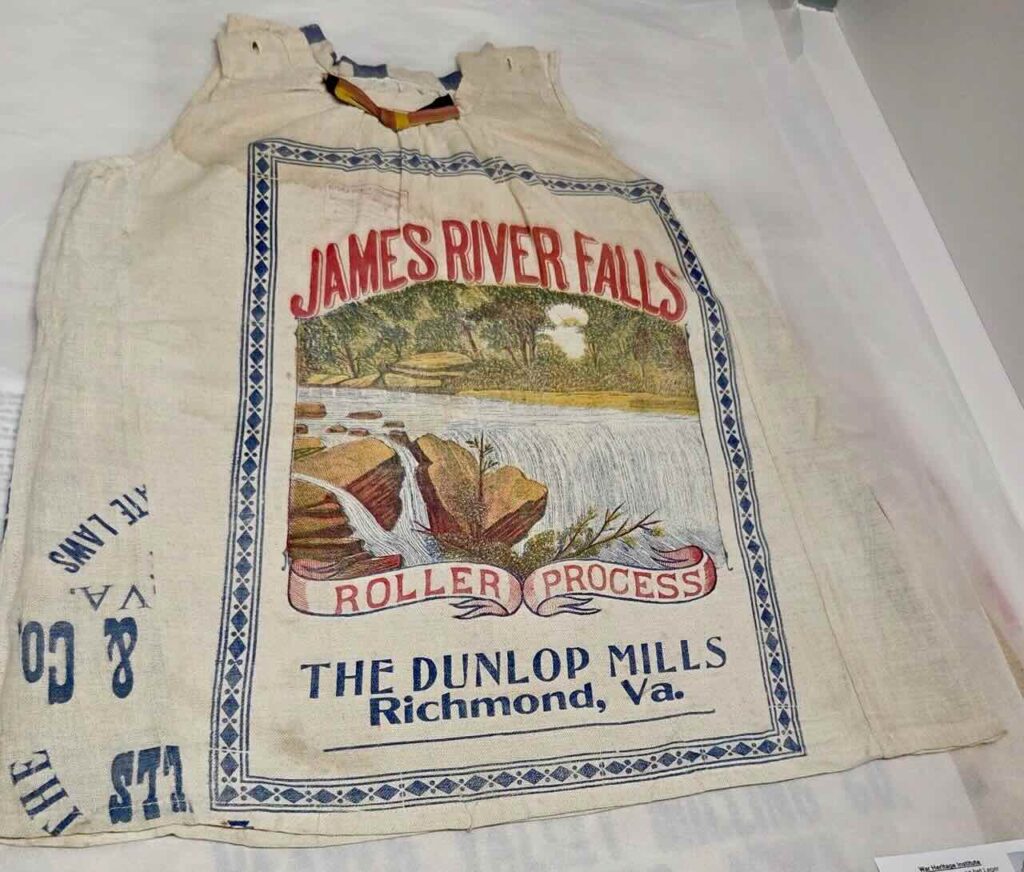

Her own “Madame Vandervelde Fund” would emerge during her impressive six-month tour in the US and Canada. She was welcomed with open arms and enthusiasm. She traveled from Syracuse to Chicago, then to St. Paul and Minneapolis. She gave speeches in the major cities of Canada. [6] She was particularly successful in collecting money in Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston. Friends in Buffalo helped her to send food aid to Belgium: flour packed in cotton sacks, which could be used to make clothes after washing and bleaching. These friends also made sure that the name “Madame Vandervelde Fund” was printed on the flour sacks.

Flour sacks that testify today to the determination of a wartime woman.

To be continued.

(See my blogs: Madame Vandervelde Fund 2 and Madame Vandervelde Fund 3)

“Sacks are full of memories. Every sack houses a fragile and precious story.”

– My sincere thanks to Evelyn McMillan, Stanford University, for the information and photos she provided to me. She mentioned Isabel Anderson’s book The Spell of Belgium and sent the New York Times article of September 2, 1914. She also sent pictures of decorated flour sacks in the collections of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Museum and the Hoover Institution Archives.

– Thanks to Hubert Bovens for his research on the biographical data of Lalla’s first husband Ferdinand Kufferath. Ferdinand was director of Société anonyme des Carrières de Porphyre de Quenast (les Almanachs de Bruxelles).

*) Sources for this photo:

– Vermandere, Martine, Madame Lalla Vandervelde. A very exceptional woman. Ghent, AMSAB IHS, 2023, p. 22,23: the photo has been published on the front page of the French magazine ‘La Vie Illustrée’, April 25, 1902, no. 184 under the heading “Le Grand Agitateur Belge – M. Vandervelde”. The caption lists the Maison de Peuple in Brussels and the names of the German Socialist deputies: Albert Sudekom (standing left) and Sigmund Haller von Hallerstein (seated left). M. Pierre was the photographer.

– Belgian written newspaper articles from April 1902 show that the photo will have been taken in the evening of April 18, 1902. Emile Vandervelde gave a speech and greeted the two German socialist friends in the room. He did not mention their names, to protect them from possible reprisals by the Belgian government.

“La soiree de vendredi. Le meeting de la Maison du Peuple. ….

Vandervelde, au nom de la solidarité internationale, salue deux députés socialistes allemands présents. (longue acclamation). Je ne les nommerais pas, car je connais trop l’hospitalité du gouvernement belge pour n’être pas prudent. Mais je vous dis qu’ils souffrent de vos souffrances et je les prie d’aller dire notre merci fraternel à nos vaillants compagnons allemands. (Ovation). Avec de tels appuis et de telles forces, la grêve continuera.”

(Le Peuple, April 19, 1902, p.2)

(Translation: “Friday Evening. The meeting in the House of the People. ….

Vandervelde, in the name of international solidarity, greets two German socialist deputies present. (long cheer). I won’t name them, because I know the Belgian government’s hospitality too well not to be careful. But I tell you that they suffer from your sufferings and I beg them to go and say our fraternal thanks to our valiant German companions. (Ovation). With such support and such forces, the strike will continue.”)

Notes:

[1] L’étoile belge, August 6, 1914

[2] Le Soir, August 16, 1914; Le Peuple, August 15, 1914

[3] L’Indépendance, September 5, 1914

[4] Vandervelde, Lalla, Monarchs and Millionaires. London: Thornton Butterworth Limited, 1925

[5] Williams, Jefferson and ‘Mayfair’, The Voluntary Aid of America. New York, London: 1918

[6] Anderson-Weld Perkins, Isabel, The Spell of Belgium. Boston: The Page Company, The Colonial Press, C.H. Simonds Co., 1915