The “Ouvroir” of Antwerp employed thousands of girls and women during the occupation of Belgium. Clothing was made and altered, shoes were repaired and flour sacks were embroidered there.

The meaning of an “ouvroir” is: “Lieu réservé aux ouvrages de couture, de broderie…, dans une communauté”; translated: “Place for sewing, embroidery …, in a community”. In a historical context, I would call it a “communal sewing workshop”.

The history of the Ouvroir of Antwerp has become familiar to me through three primary sources: one Belgian and two American.

– “Heures de Détresse” by Edmond Picard, the Belgian primary source shows some photos of the Ouvroir.[2]

– “War Bread” by Edward Eyre Hunt commemorates the Ouvroir of this American delegate of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) in the province of Antwerp. He was a young journalist and writer; he worked in Antwerp from December 1914 to October 1915.[3]

– “Women of Belgium” by Charlotte Kellogg, née Hoffman (Grand Island, Nebraska, 1874 – California 08.05.1960). She was also a CRB delegate – unique as the only woman – and stayed in Belgium between July and November 1916. As a writer and activist, she committed herself to the good cause of Belgian women.[4]

Edward Hunt, War Bread

In the autumn of 1914, three women took the initiative to set up a clothing workshop to provide assistance to residents of the city of Antwerp.

- Laure de Montigny-de Wael (Antwerp 29.11.1869 – Ixelles, Brussels 09.07.1926)

- Anna Osterrieth-Lippens (Ghent 01.11.1877 – Brussels 14.09.1957)

- Countess Irène van de Werve de Vorsselaer-Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem (Ghent 17.12.1857 – Antwerp 21.04.1938)

They headed a committee of ladies who, I assume, had experience in the organization of charities and workhouses. Even before the war, there were numerous private initiatives offering employment and education to young women and assistance to needy people. The committee is said to have bought up all the piece goods it could find in the city and commissioned the Folies Bergères theater to employ hundreds of young women to make and repair clothes.

Rockefeller Foundation

The American Rockefeller Foundation collected clothing in the US and shipped it via the port of Rotterdam to Belgium. Canada also provided clothing transports.

Citation from ‘War Bread’: ‘‘Before January first, 1915, the Rockefeller Foundation contributed almost a million dollars to the work of Belgian relief, and established a station in Rotterdam called the Rockefeller Foundation War Relief Commission, to assist the Commission for Relief in Belgium. This station had charge of the sorting and shipping of clothes sent from America for Belgium.

We never had enough to supply them. It was only when the generous gifts of clothing began to come from America through the Rockefeller Foundation War Relief Commission, that the situation improved at all.”

The Ouvroir was under the protection of the CRB and received a monthly subsidy of 50,000 francs from the city of Antwerp until the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (CNSA) took over financing.

The Ouvroir moved to larger premises: the “Winter Hall” in the Arenbergstraat of the Société Royale d’Harmonie. [5]

The Ouvroir in the Winter Hall, “Harmonie”

Hunt paints this picture of the organization of the Ouvroir: ‘‘The stage of the Antwerp Harmonie was piled with boxes of goods. Galleries and pit were spread with rows of sewing machines and work tables, and the cloak room was transformed into a steam and sulphur disinfecting bath, where all materials, new and old, were taken apart and thoroughly cleansed. Nine hundred girls and young women worked under supervision in the warm, well-lighted hall, while about three thousand older women were given sewing to do at home.

A group of cobblers in the hall made and repaired shoes. All these workers were paid. From the central workshop, made goods and unmade materials were sent throughout the Province; the latter to sewing circles in the villages and towns.”

Charlotte Kellogg: Women of Belgium

Charlotte Kellogg went to visit the workroom.

“We looked on a sea of golden and brown heads bending over sewing tables. Noble women had rescued them from the wreckage of war—within the shelter of this music-hall they were working for their lives… 1200 girls were preparing the sewing and embroidery materials for 3,300 others working at home. In other words, this was one of the blessed ouvroirs or workrooms of Belgium.

Here the whole attitude toward the clothing is from the point of view, not of the protection it gives, but of the employment it offers. Without this employment, without the daily devotion of the wonderful women who have built up this astonishing organization…. Of course, there is always dire need for the finished garments. They are turned over as fast as they can be to the various other committees that care for the destitute. Between February 1915, and May 1916, articles valued at over 2,000,000 francs were given out in this way through this ouvroir alone.”

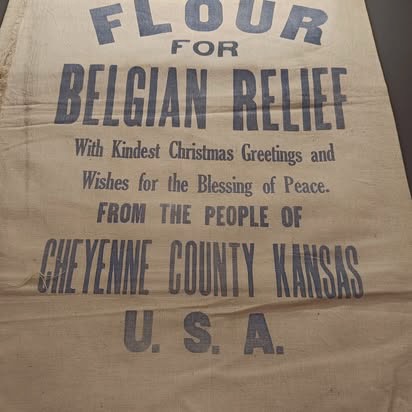

Transformation of flour sacks

Kellogg did not mention whether flour sacks were transformed into clothing in the Ouvroir, probably not. However, some of the women were involved in embroidery!

The embroidery of the flour sacks in the Ouvroir caught Kellogg’s attention:

“In one whole section the girls do nothing but embroider our American flour sacks. Artists draw designs to represent the gratitude of Belgium to the United States. The one on the easel as we passed through, represented the lion and the cock of Belgium guarding the crown of the king, while the sun—-the great American eagle rises in the East. The sacks that are not sent to America as gifts are sold in Belgium as souvenirs”

The workers’ reward was training in sewing and pattern design; lessons in history, geography, literature, writing and special attention to hygiene, plus a payment of 3 francs per week. Kellogg exulted: “These things are splendid, and with the three francs a week wages, spell self-respect, courage, progress all along the line. The committee has always been able to secure the money for the wages”

Countess Irène van de Werve de Vorsselaer-Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem

Last week I received a message from one of the great-grandsons of Countess Irène van de Werve de Vorsselaer-Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem, a committee member of the Ouvroir. I had previously come into contact with Mr. van de Werve de Vorsselaer in my research into the maiden name of “Comtesse van de Werve de Vorsselaer” and her involvement in charitable committees. His great-grandmother turned out to have been very active in charity works during the war.

“The Countess van de Werve de Vorsselaer in question was born Irène Kervyn d’Oud Mooreghem. She married Count Léon van de Werve de Vorsselaer (1851-1920) on April 23, 1877 in Mariakerke. They had two sons.

She was a member of the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, of the Association des Mères Chrétiennes and of L’Hospitalité de Notre-Dame de Lourdes. She was also a Knight of the Order of Leopold II with a silver star and was awarded the Commemorative Medal of the 1914-1918 War (France) and the Victory Medal. She was presented these awards due to her boundless dedication to the war wounded: she had comforted them, eased their pain and cared for them in the halls of the Antwerp Zoo, which for the occasion had been transformed into an improvised military hospital.” [6]

The message I just received from Mr. van de Werve de Vorsselaer contained a surprise. He had talked to his wife about our conversations and she remembered that his mother had given her some decorated flour sacks. To his surprise, three embroidered flour sacks had emerged, the existence of which had been unfamiliar to him.

He was so kind as to send sent me photos of the embroideries.

Embroidered flour sack ‘Ouvroir d’Anvers’

Examination of the photos made me jump for joy: one of them was embroidered in white on white: “Ouvroir d’Anvers. Années de Guerre 1914-1916 “. The original printing of the flour sack is missing, but in size it is the canvas of half a flour sack. Undisputedly a craft that originated at the Ouvroir of Antwerp!

It is a small tablecloth with floral motifs, decorated with scalloped edges throughout, executed in white embroidery techniques, the style resembles English embroidery.

Seeing as one flour sack had originated at the Ouvroir, I assume that the other two embroideries were also created there. These flour sacks have been transformed into cushion covers.

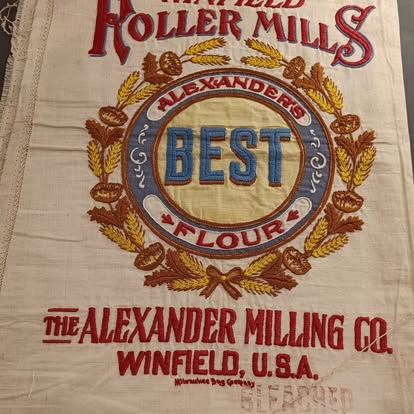

Quaker City Flour Mills Co., Philadelphia

The origin of one flour sack is the “Quaker City Flour Mills Co., Philadelphia”, from the state Pennsylvania. The characters of the original print are embroidered in the colors red, yellow, black and red, white, blue. Some small flags have been added as patriotic decoration, as well as the years 1914-1915-1916-1917. The result is a colorful cushion cover.

American Commission

One flour sack originates from the “American Commission”. The original print was blue, but that color has faded. This decorated sack also features the white embroidery techniques; it looks like Italian embroidery. The contours of the characters are embroidered with white yarns. Furthermore, the flour sack has been artfully decorated with leaves and flowers.

Finally

Mr. van de Werve de Vorsselaer stated in his explanation accompanying the photos of the flour sacks that he knew of neither the existence nor the background of their collection of decorated flour sacks. He thanked me with: “Grâce à vous, mes enfants et petits-enfants sauront leur provenance.” (“Thanks to you, my children and grandchildren will know their origins.”)

In turn, I would like to thank Mr. and Mrs. van de Werve de Vorsselaer. My research questions: who embroidered the flour sacks, where did they embroider them, what was their motivation, have received meaningful answers. Thanks to the collection of three embroidered flour sacks, the work of great-grandmother van de Werve de Vorsselaer and of thousands of other girls and women in the Ouvroir of Antwerp came back to life.

Sequels

– For the sequel see the next blog: The “Ouvroir” of Antwerp (2)

– *) I published a third blog (on February 17, 2021) about the flour sack “Rooster on oak branch at dawn” designed by the Belgian artist Piet Van Engelen and embroidered in the Ouvroir d’Anvers.

– A fourth blog on the Antwerp flour sacks: Olga Kums’ beschilderde bloemzak (Olga Kums painted flour sack).

[1] My thanks go to

– Mr. and Mrs. van de Werve de Vorsselaer for their information and the photos of the decorated flour sacks;

– Hubert Bovens in Wilsele for providing biographical data;

– Majo van der Woude of Tree of Needlework in Utrecht for her advice on the various embroidery techniques;

– Jacob Ulens, freelance historian, photographer and author. He conducted research into the premises of the Société Royale d’Harmonie. He wrote to me: “The photos of the Ouvroir were definitely taken in the Winterlokaal (Winter Hall) located in the Arenbergstraat. It was one of the largest, perhaps the largest, dance hall in Antwerp. The Winter Hall is clearly recognizable in this 3D reconstruction. ” (email message 2022.12.06)

[2] Picard, Edmond, Heures de Détresse. L’Oeuvre du Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation et de la Commission for Relief in Belgium. Belgique 1914 – 1915. Bruxelles: CNSA, L’ Imprimerie J -E Goossens SA, 1915

[3] Hunt, Edward E., War Bread. A Personal Narrative of the War and Relief in Belgium. New York: Henry Holt & Company 1916

[4] Kellogg, Charlotte, Women of Belgium. Turning Tragedy in Triumph. New York and London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 4th edition, 1917

5] The Royal Harmony had two locations: the Winterlokaal (Winter Hall), dance/concert hall in the city center on Arenbergstraat/Rue d’Arenberg and the Zomerlokaal (Summer Hall) on Mechelsesteenweg/Chaussée de Mailnes in the Harmonie Park, adjacent to the current King Albert Park.

The Ouvroir was definitely located in the Winter Hall; it used the Summer Hall for a short time (read: Hunt, War Bread, Appendix XXIX, The Clothing Workshop, p. 357).

[6] The rooms of the ZOO were made available to the Red Cross in 1914.

Count Léon van de Werve de Vorsselaer had been involved in the management of the Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp since 1902 as administrator. In 1919 he became chairman of the board, but died unexpectedly in 1920. It appears both spouses, like many prominent and noble families, had a close relationship with the famous Antwerp Zoo. Baetens, Roland, The chant of paradise. The Antwerp Zoo: 150 years of history. Tielt: Lannoo, 1993