The Europeana Collections website 1914-1918 put me on the trail of this unique photograph of two young, Belgian embroiderers, plus two decorated flour sacks in a private collection [1].

In the online contribution “Oscar De Keersmaecker from Oppuurs”, his son Jozef talks about his father’s experiences as a soldier in WWI and the burning down of his father-in-law’s mill in 1914. Jozef De keersmaecker is Honorary Alderman of Oppuurs, he is also a writer of historical books, including the “History of Oppuurs 1311-2003”.

This story “Thanks from Oppuers” (“Oppuers” is the old spelling of “Oppuurs”) brings together a Belgian and an American mill.

Oppuurs, part of the municipality Puurs-Sint-Amands, is located in the province of Antwerp. I traveled there in November, Mr. and Mrs. De keersmaecker-Verbruggen were so kind to welcome me in their home to study the decorated flour sacks and shared with me the accompanying family stories.

The mill of Oppuurs was originally a wooden grain windmill, which was founded before 1508. In 1887, miller Petrus Edmond Verbruggen inherited the mill from his deceased wife. Verbruggen remarried Maria Rosalia Van Der Linden; when he died in 1907, he left the mill to his wife and children.

In the meantime, during a storm in 1898, the standard mill had been toppled, but had been rebuilt in 1901 as a “belt mill” with a fairly high base, grounded on a slope. After the outbreak of the First World War, fate struck again. The Belgian army set fire to the mill: the mill would obstruct the view from the Bornem fort of the advancing German troops; and if they would advance, the mill could not serve as a lookout post for them.

The mill was never rebuilt on the spot, the only thing that reminds us today is the mill well. [2]

The miller’s family Verbruggen went with the times, in 1917-1918 they founded a new steam mill at Oppuurs station. After years of back and forth, the Belgian state eventually paid compensation for the destruction of the mill.

A lot of needlework has been done in the family of Rosalie Verbruggen-Van Der Linden. The girls went to school in Oppuurs and were educated by the nuns of Annonciaden from Veltem; by far the majority of people in the village owe part of their upbringing to these nuns.

A lace school was founded in 1912.

Antoinette and Irena Verbruggen made a diptych on flour sacks with the image of the family mill in operational and destroyed condition: “Praise and Thanks Oppuers 1914” and “America Relief in Need 1915”. It was hemmed with a wide strip of lace and decorated with band and brushes. It must have been a colorful needlework.

The girls proudly showed their work in the photo. On the back of the photo is written: ”L. Irène Verbruggen, R. Antoinette Verbruggen, sisters, aunts of Jeanneke Verbruggen. These sacks were a memento as a thank you for the American help. They are flour sacks and are owned by the Verbruggen family.”

Unfortunately, it is not known whether the decorated flour sacks on the photograph have been preserved.

The entire Verbruggen-Van Der Linden family was portrayed during the photo session, nine children were still alive. The two boys, Modest and Frans, are on the left and right of their mother Rosalie; they would continue the business. Irena and Antoinette would later enter the monastery as nuns.

Sister Rozalia, daughter of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, Antonia Verbruggen (Oppuurs 1898.06.27 – Rumst 1989.07.07) was professed in Opwijk on August 25, 1929.

Her sister Irena Verbruggen (Oppuurs 1893.06.19 – Ternat 1984.03.09) entered the Ursuline sisters in Mollem on August 16, 1917 and took her perpetual vows there on October 21, 1925; her name was Sister Edmond.

Two other sisters Verbruggen, Maria and Louise, became teachers with permanent appointments at the elementary school in Oppuurs.

There are two well-preserved flour sacks in the family. After the death of Frans Verbruggen, his eldest daughter Jeanne and her husband Jozef De keersmaecker dicovered the sacks at his home.

I have written about one of these decorated flour sacks before, in my blog “Verwondering over een Koene Held” (“Marvel of a Valiant Hero”).

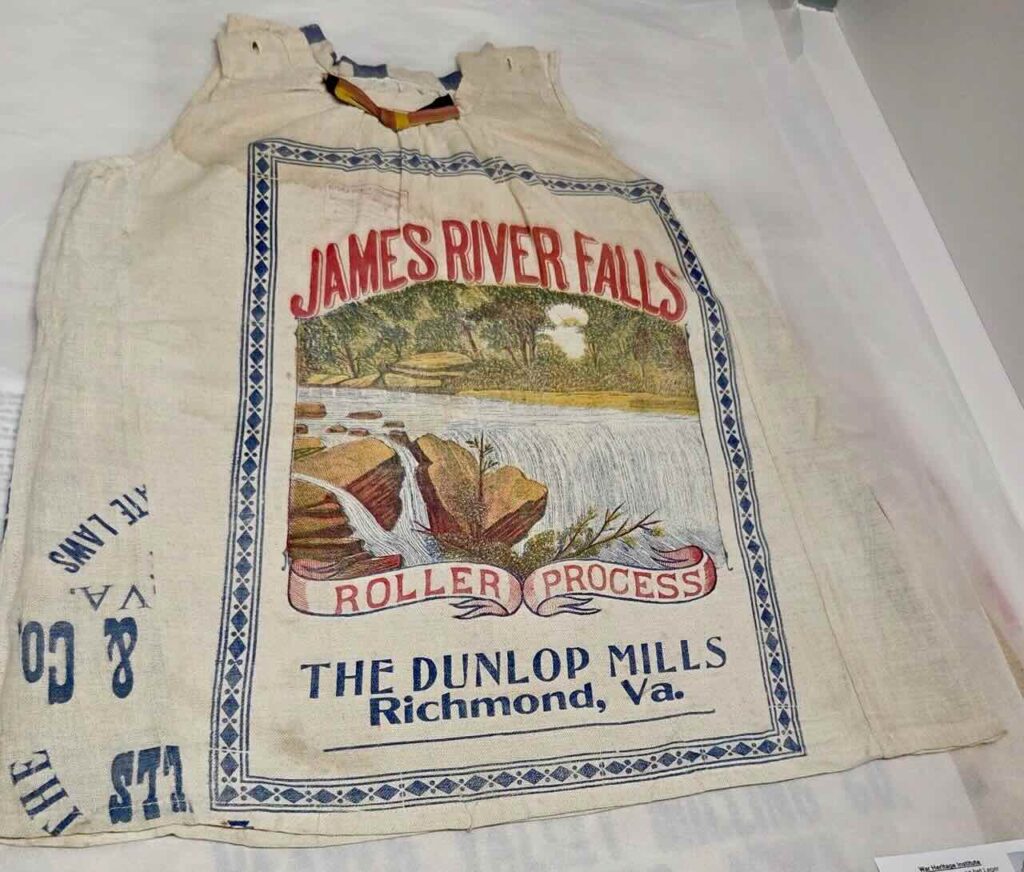

“Dank van Oppuers” (Thanks from Oppuers) is written in capital letters on the flour sack from Wheatland Roller Mill Co. in Wheatland, Wyoming, USA. The sack “Belgian Relief Flour” arrived in Belgium in March 1915 through the relief campaign “The Miller’s Belgian Relief Movement 1914-15” from the Northwestern Miller, the magazine of American millers in Minneapolis [3].

In the fall of 1914, the people of the state of Wyoming raised money for the needy Belgian population. To contribute to the Miller’s Belgian Relief Movement flour was purchased from the Wheatland Roller Mill Co., as reported in the relief effort Report.

The flour mill existed from 1897 to 1931 [4]. The town of Wheatland commemorates the history of the mill to this day with a mural in the city center, applied in 2017 by the “Platte County Art Guild”.

The steamer “South Point” transported a load of 6200 tons of relief goods for a value of $ 500,000 from Philadelphia to Rotterdam. The ship arrived safely in the port of Rotterdam on 27 February 1915, where the sacks of flour were immediately loaded on inland vessels and shipped to Belgian ports. A number of barges sailed to Antwerp; hence the flour would be distributed to Oppuurs.

Empty sacks will have been handed over to the Annonciaden Sisters’ Monastery School in Oppuurs, where the schoolgirls processed the flour sacks in class as part of their needle training.

On the unprinted side of the flour sack, first a design would have been made and the pattern drawn, in some places you can still see blue lines on the canvas. The embroidery is meticulously executed, as well as the wide lace border, see the appendix with the complete inventory of the flour sack.

Remarkable are:

- The three buttonholes

- The year “1915” as the year of decoration, instead of a timeline 1914-1915

- Europeana Collections 1914-1918 mentions the contribution of Henri Vertongen including the image of a correspondingly decorated flour sack with “Thanks from Puers”. See my blog of January 23, 2020.

My warm thanks go to Jozef De keersmaecker and his wife Jeanne Verbruggen. She is the granddaughter of Rosalie Verbruggen-Van Der Linden and has always known her grandmother as an independent, decisive woman. Jeanne’s aunts, who became nuns as adults, embroidered the dyptich of flour sacks with the mills when they were schoolgirls.

Who knows they and the other sisters Verbruggen may also have worked on the two flour sacks preserved by their brother Frans.

ADDITION November 5, 2021

In the collection of the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University, the Ben S. Allen Collection contains a flour sack “Belgian Relief Flour Pillsbury Flour Mills“, donated by the local Oppuers relief committee. The members of the committee have placed their signatures under the photos of King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth.

Between them an embroidered lion is staring a bit dejectedly. The US and Belgium flags and the Oppuers coat of arms are embroidered; a wide strip of lace forms the edge decoration. ‘M.Mees’ is the signature of the embroiderer. Maria Josepha Isabella Mees ( Oppuurs 1901.02.08 – Beerse 1976.12.06) was 14 years old when in 1915 she applied the decorations for the relief committee to the flour sack. She was the daughter of the municipal teacher Jan Mees and Maria Van Assche. Later Maria Mees married Dirk Vancoppenolle (Essen 1895.05.20 – Beerse 1978.08.21); he was a doctor in Germanic philology, a teacher at the Royal Athenaeum.

Evelyn McMillan reports about Benjamin S. Allen: “he was a Stanford University graduate, a friend of Hoover’s, an American journalist based in London, and helpful in writing about the situation in Belgium during the war to tell the world what was going on and what was needed”. Writing for the Associated Press, Allen was CRB delegate from October 1914 until the end of CRB’s operations.

The members of the Oppuers relief committee were: Frans van Damme, Schepene on-duty Mayor (chairman); Jan Mees, Schepene; E. Lauwers; J. Slachmuylders; J. Hulsbosch; H. Stevens; Ed. Willocx; Alberie Theyskens, curate in Oppuers, (secretary treasurer); Joseph Van Assche, rentier; Modeste Verbruggen, miller.

Thanks to:

– Evelyn McMillan for making the flour sack photos available in the Ben S. Allen Collection at HIA;

– the members of the Facebook group Lizerne Trench Art (LTA), Jorn van Bulck and Ingo Luypaert, for their help in identifying the names of the Oppuers relief committee;

– Bart Palmans of Heverstam, Historical Collecting Circle Sint-Amands;

– Hubert Bovens, Wilsele, for the search for biographical information;

– Patricia Quaghebeur of KADOC, Louvain, for the biographical details of Sister Edmond/Irena Verbruggen.

Footnotes:

[1] The decorated flour sacks “Dank van Oppuers” and “Koene Held” have been on display to the public at Heemkundige Verzamelkring (“Historical Collecting Circle”) Sint-Amands HeverStam during the exhibition “The face of the Great War” in 2018

[2] The history of the mill of Oppuurs is described in the Molendatabase.EU: see the collection “Lost Belgian Mills”

[3] See also my blog / article “A Famous Flemish Flour Sack in The Land of Nevele” of 25 October 2018

[4] More about the history of Wheatland Roller Mill Co. in the book by Starley Talbott, Platte County. Images of America. Charleston SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009