One of the goals of my research is to unravel the mythical history of the origins of the decorated Flour Bags in WWI. Decorated Flour Bags in WWI have been embroidered, decorated with needlework, with lace, as well as painted on by artists. Flour Bags have been transformed into clothing.

Who had the idea of reusing these bags? Where and when did that start? Was it a Belgian initiative or was it due to strong American suggestions?

Belgian newspapers and magazines

To find answers to my questions, I systematically went through a number of Belgian newspapers and illustrated magazines from the end of 1914, beginning of 1915; these have been digitized and are online.

I had already found some American publications and combined them with the Belgian information.

I have split my analysis and findings into four parts:

- Reuse of Flour Bags into clothing.

- Transformation of Flour Bags with embroidery, needlework and lace into decorated Flour Bags, Belgian primary sources, see blog May 26, 2019

- Transformation of Flour Bags into painted decorated Flour Bags, Belgian primary sources, see blog September 9, 2020 and blog September 11, 2020.

- Transformation of Flour Bags into decorated Flour Bags, American primary sources.

Reusing Flour Sacks as clothing

Photo-collage, Annelien van Kempen, 2022

In this blog I will discuss the origin of the reuse of Flour Bags as clothing. Two primary sources bear witness to this.

1) January 1915: Madame Lalla Vandervelde

A source with information I found is an article in a Belgian newspaper that was published abroad, about Madame Vandervelde.. Her maiden name was Charlotte “Lalla” Speyer, British by birth and from German parents, she was married in 1901 to her second husband, the Belgian Minister of State, Emile Vandervelde. The couple divorced some years after WWI. [1]

Since October 1914, Madame Vandervelde had been in the United States to ask for help for the Belgian population in need. In Buffalo, New York, she gave a lecture and received 10,000 bags of flour as a gift. The bags were made of fine cotton and intended for reuse.

La propagande pro-belge aux États-Unis.

‘Madame Vandervelde, la femme du Ministre d’Etat, est aux États-Unis depuis plus de trois mois. Elle y a donné et y donne sur la Belgique et les horreurs, dont elle a été victime, une série de conférences qui ont le plus grand succès et dans lesquelles on acclame la Belgique et les Belges. …..

A Buffalo, des industriels lui ont offert un bâteau chargé de 10.000 sacs de farine, – sacs confectionnés en fine toile et en étoffe, afin qu’ils puissent servir par la suite et être transformés en vêtements et en linges pour les habitants. …

Translation: “In Buffalo, manufacturers have donated to her a ship with 10,000 bags of flour – bags made of fine canvas and cloth, so that these can afterwards be used and transformed into clothing and towels for the inhabitants…. “

The Committee in Buffalo had the flour bags printed with the text “War Relief Donation Flour from Madame Vandervelde Fund”. Lalla Vandervelde did not set up a fund herself. The donations she received were handed over to the Belgian Relief Fund in the US. In Belgian collections there are flour bags with the original “Madame Vandervelde Fund” prints:

a) the unprocessed Flour Bag on a photo of a Flour Bags-collage, provided to me by the In Flanders Fields Museum (IFFM), Ypres, with the text: “War Relief Donation Flour from Madame Vandervelde Fund – Belgian Relief Fund, Buffalo, N.Y. U.S.A. 49 Lbs.”[2]

b) the decorated Flour Bag, which I see online at the ‘Ieperse Collecties’ (Ypres Collections). Object number IFF 003008 is an “Embroidered and painted Flour Bag attached on a stretcher with the text “War Relief Donation – Flour 1914-1915 – from Madame Vandervelde Fund “. At the top the portrait of Emile Vandervelde, Minister of State of Belgium.”

2) November 1914: Mr. William C. Edgar

The earliest American source on the reuse of Flour Bags as clothing comes from Mr. William C. Edgar, editor-in-chief of the American newspaper “The Northwestern Miller” in Minneapolis, Minnesota. On November 4, 1914, he started the aid campaign “The Miller’s Relief Movement”. [3] The newspaper, a trade magazine for grain millers, made a request to subscribers and advertisers, in particular the flour mills, to donate flour for Belgium’s aid. The quality of the flour was specified in detail and the packaging had to meet the following conditions: cotton bags, sturdy for transport, dimensions suitable for handling by one person and last but not least “suitable for reuse“:

The earliest American source on the reuse of Flour Bags as clothing comes from Mr. William C. Edgar, editor-in-chief of the American newspaper “The Northwestern Miller” in Minneapolis, Minnesota. On November 4, 1914, he started the aid campaign “The Miller’s Relief Movement”. [3] The newspaper, a trade magazine for grain millers, made a request to subscribers and advertisers, in particular the flour mills, to donate flour for Belgium’s aid. The quality of the flour was specified in detail and the packaging had to meet the following conditions: cotton bags, sturdy for transport, dimensions suitable for handling by one person and last but not least “suitable for reuse“:

“Instructions were issued at the same time for packing the flour. These stipulated that a strong forty-nine pound cotton sack be used. This was for three reasons: the size of the package would be convenient for individual handling in the ultimate distribution; the use of cotton would, to a certain extent, help the then depressed cotton market, and finally and most important, after the flour was eaten, the empty cotton sack could be used by the housewife for an undergarment, the package thus providing both food and clothing. ‘(Final Report: The Miller’s Belgian Relief Movement 1914-1915, p. 9). [4]

“Instructions were issued at the same time for packing the flour. These stipulated that a strong forty-nine pound cotton sack be used. This was for three reasons: the size of the package would be convenient for individual handling in the ultimate distribution; the use of cotton would, to a certain extent, help the then depressed cotton market, and finally and most important, after the flour was eaten, the empty cotton sack could be used by the housewife for an undergarment, the package thus providing both food and clothing. ‘(Final Report: The Miller’s Belgian Relief Movement 1914-1915, p. 9). [4]

Tradition

The motive for reuse was widely used among the American female population. Reuse of cotton bags had already been established for decades and earlier. Cotton was a product of the country, bags were usable pieces of cotton. It provided the sparing housewife with simple items of clothing for free or for a low price. After good washing, the seamstresses cut the pattern of the clothes out of the bags and mainly made undergarments for their own family. After the First World War, the reuse of cotton bags developed further in the US from the 1920s.

During the depression in the 1930s, the Americans protected their distressed cotton industry, reusing cotton bags was a sign of frugality and also a patriotic duty. Product development and marketing efforts by bag suppliers resulted in washable prints, washable labels and finally colorful, fashionable and hip prints on the bags. In the 40s and 50s it was particularly fashionable to wear garments made from bags. A true “Feedsack” cult prevailed among rural women to sew clothes from used cotton bags that had served as packages of chicken feed, flour, sugar and rice for the entire family. [5]

No Belgian, but an American source

There are sewing workshops who have made functional underwear, aprons and jackets with recycled flour bags, usually for children, according to the American writer Charlotte Kellogg who stayed in Belgium from July to November 1916.

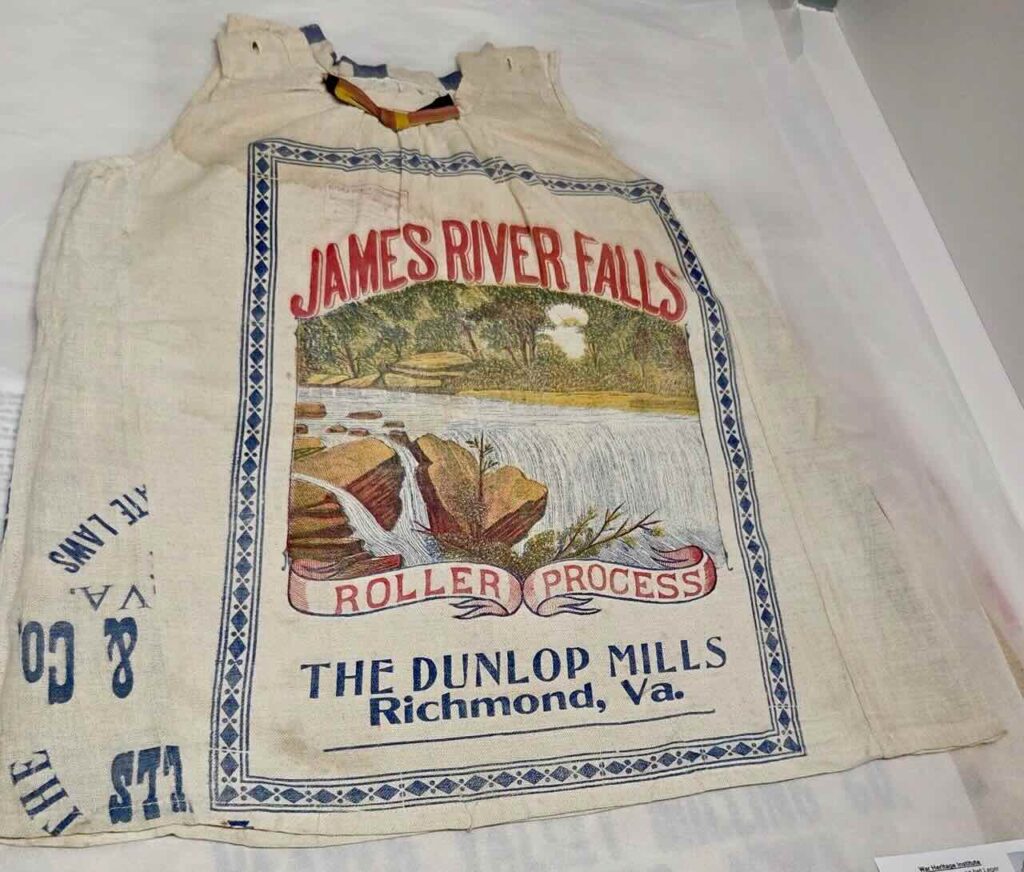

Remarkably, I don’t know any Belgian written source about sewing workshops reusing the flour bags for clothing. However, there are photos on which young girls can be seen, dressed in attractive aprons and dresses, outerwear on which proudly the brand name of the mill and the inscriptions of the aid organizations are shown.

In my research I have not yet come across flour sack clothes in any Belgian collection. Well in two American: a few dozens of pieces of underwear, aprons, a jersey and pants in the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Museum (HHPLM), a few pieces of embellished children’s clothing in the Hoover Institution Library Archives (HILA).

In Heverlee, 80 children, mostly girls from around 4 to 6 years old, were photographed, dressed in Flour Sacks with the “American Commission” logo.

Mr. Robert Bruyninckx shared this black and white photo of 14 × 9 cm in the Europeana Collections under the title: “Group photo with children dressed in clothes made from bags of the American Commission for Relief in Belgium.”

Description: “Group photo with Jeanne Caterine Charleer (born in Heverlee on August 17, 1910), top row, 7th from the right. Children dressed in clothes made from bags of the American Commission for Relief, with the American flag in the background. The photo is a family piece. Jeanne Caterine Charleer was the mother of Robert Bruyninckx.”[6]

A girl was photographed in a “Belgian” dress with the “Sperry Flour” logo from California.

Conclusion

Although I have only found two primary sources, I nevertheless come to the conclusion about the origin of the reuse of Flour Bags as clothing: this practice was taken up in Belgium at the strong suggestions of American relief workers.

The Flour Bags were special to the Belgians, they made, apart from undergarments, also nice dresses for their children.

[1] Gubin, Eliane, Dictionnaire des femmes belges: XIXe et XXe siècle, p. 510-512; gw.geneanet.org: “Charlotte Hélène Frédérique Marie Speyer”

[2] Delmarcel, Guy, Pride of Niagara. Best Winter Wheat. Amerikaanse Meelzakken als textiele getuigen van Wereldoorlog I. Brussel, Jubelpark: Bulletin van de Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis (‘American flour sacks as textile witnesses of World War I’. Brussels, Cinquantenaire: Bulletin of the Royal Museums of Art and History), deel 84, 2013, p. 97-126

[3] See also my blog: “A Celebrity Flemish Flour Bag in The Land of Nevele” of October 25, 2018

[4] The Millers ’Belgian Relief Movement 1914-15 conducted by The Northwestern Miller. Final Report of its Director William C. Edgar, Editor of the Northwestern Miller, MCMXV

[5] Three sources to continue reading about ‘Feed Sacks’:

– Linzee Kull McCray, Feed Sacks, The Colourful History of a Frugal Fabric, 2016/2019;

– Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, For a few sacks more, online exhibition Textile Research Centre, Leiden, 2018

– Marian Ann J. Montgomery, Cotton and Thrift. Feed Sacks and the Fabric of American Households, 2019

[6] The group photo with the children in Heverlee in clothing from bags with the logo ‘American Commission’ is printed in the article by Ina Ruckebusch: ‘Belgische voedselschaarste en Amerikaanse voedselhulp tijdens WOI’ in: Patakon, tijdschrift voor bakerfgoed, (Belgian food scarcity and American food aid during WWI’ in: Patakon, Magazine about bakery heritage) 5 nr. 1 (2014) , p. 29.