The decorated flour sacks resonate the conflict that created them. They are trench art made in occupied Belgium. They are: “items made by civilians, from war material directly as they are associated temporally and spatial with the consequences of armed conflict”.

Decorated flour sacks are sacks full of discomfort and paradox. The huge and exaggerated “Tribute to America” is one of them – it contributed to the morale of the population in occupied Belgium.*)

USA and Canada

75% of the decorated flour sacks I have found are flour sacks originating from the United States, from 10% the origin is unknown.

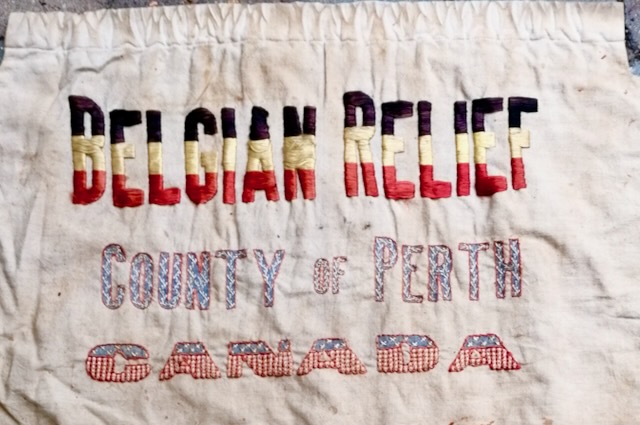

15% originated from Canada. Examples include: “Flour. Canada’s Gift; Flour Canada’s Gift, Lake of the Woods Milling Company Ltd., Keewatin, Canada; Belgian Relief County of Perth, Canada; Farine offerte par les Citoyens de Valleyfield (prov. Quebec, Canada) aux habitants de l’Héroique Belgique”, and so on: see table.

In Belgium: American flour sacks/ “sacs américains”

Yet all flour sacks are in common parlance known in Belgium as “American flour sacks” and “sacs américains”, regardless of their origin being the United States or Canada.

What is striking is that donations from Canada have been embroidered and painted by the Belgians with USA symbols, the flag, the coat of arms and the portrait of the American plenipotentiary minister in Brussels, Brand Whitlock. The texts pay tribute to “America”:

– Merci à l’Amérique

– Merci aux Etats-Unis!

– Vive l’Amérique

– A la noble Amérique si bienfaisante, la Belgique reconnaissante. Amour à notre Reine. Mère des soldats. Gloire à notre Roi. Chef de nos héros.

Some flour sacks pay tribute to Canada.

Hidden identity of Canadian flour sacks

When doing research on the flour sacks I expected the Canadian flour sacks to have been decorated in Belgium with a “Tribute to Canada”. But they are not.

Was my assumption incorrect?

Why would the Canadian identity of the sacks be hidden under USA symbolism? Six motives occur to me.

1. Were the young Belgian embroiderers and the Belgian artists unfamiliar with the distinction between the countries USA and Canada? This is unlikely because they belonged to the wealthy part of the population and were well educated. Furthermore, they knew that Canadian soldiers were fighting on the side of the Allies.

2. Or, a practical consideration: did the Belgian food committees prefer to keep the real, original, American flour sacks for themselves? Did they therefore make a surplus of the Canadian flour sacks available to be transformed into war souvenirs destined for America?!

3. Would the import of Canadian foodstuffs have raised questions with the German occupier? Canada had joined the war following its mother country Great Britain; the United States was neutral and would not join the war until April 1917.

4. Could it have been the influence of American journalists and war photographers? They were allowed to move freely in occupied Belgium. Their Canadian, British and French colleagues were gone. The American newspapers had been involved in extensive relief campaigns for “Poor Little Belgium”. Their journalists in Belgium were encouraged to send proof of receipt of provisions in convincing, visible expressions of gratitude.

Were the Canadian benefactors not interested in Belgian thanks?

5. Or does it emphasize that for citizens in occupied Belgium, the tribute to America was all-encompassing propaganda through which they fulfilled their patriotic duty as they could express themselves in patriotism? Was it the counterpart of the general propaganda abroad shaping a dramatic “Poor Little Belgium” image of a devastated country? At the beginning of the conflict, such exaggerations helped to arouse public sympathy for the Belgian cause.**)

6. Did the ambiguous attitude of the British play a role?

Great Britain, in control of Canada’s foreign affairs, had militarily put itself on the front line as protector of the nation of Belgium, welcomed Belgian refugees, but abandoned the population of occupied Belgium. In fact, the mighty British nation prevented the much-needed access to food through a complete trade blockade and sea mines in front of all Belgian ports. Could the Canadian identity have been hidden due to the antipathy for its relationship to the United Kingdom?

Anyway, the sympathy of the citizens in occupied Belgium went to the nation they expected to rescue them: “America”.***)

“America would save us”

Belgium was occupied by Germany in August 1914, the borders were closed, the trade blockade of Great Britain made import of bread grain impossible. Diplomatic negotiations with neutral countries opened the borders for food supplies.

‘Mais non, le pays ne pouvait pas mourir, ne voulait pas mourir. (…)

l’Amérique avait donné l’espoir qu’elle nous sauverait…’[1]

(‘But no, the country could not die and would not die. (…)

America gave us hope that it would save us…’)

Cargoes of American and Canadian bread flour arrived in Belgium via the port of Rotterdam between November 1914 and May 1915. To protect the supplies from being seized by the German occupiers, the provisions were stored in Belgium under the protection of the neutral USA flag and American citizens were stationed in occupied Belgium to supervise.

The supplies of bread flour were delivered successively to Belgian bakeries, they emptied the flour sacks and baked bread.

The emptied, attractively printed “American” sacks caught the attention of the public. The conviction was that the senders of the sacks – the benefactors in “America” – had guaranteed the survival of the Belgian people.

Background to the food imports

In October 1914, the Belgian Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (CNSA) had found itself in London to enable the import of food in occupied Belgium. Their partner in the effort became the international, private, purchasing agency, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), based in London, Great Britain, but staffed by European-based “neutral” Americans. [1A]

According to high-minded Belgian expectations, the CRB would perform a dual task:

(…) c’est lui qui provoquera l’esprit de solidarité et la générosité mondiale et amassera les trésors qu’on lui enverra; c’est lui qui dirigera vers la Belgique les dons en nature qu’il aura reçus et les vivres qu’il aura achetés pour elle.[2]

(1. “(…) the Commission will arouse the spirit of solidarity and universal generosity and gather the treasures that will be sent to it;

2. the Commission will remit to Belgium the donations in kind that it has received and the food that it will buy with them.”)

‘Reconnaissance pour les Etats-Unis

Les délégués américains et espagnols de Londres et Bruxelles ont réussi de faire importer en Belgique, malgré la guerre des grains et autres produits alimentaires. Nous leur en sommes très reconnaissants et dans ce conflit européen, la diplomatie n’a executé de plus bel et plus noble ouvrage.’[3]

(Despite the war the American and Spanish delegates from London and Brussels have succeeded in importing grain and other food products into Belgium. We are very grateful and in this European conflict, diplomacy has been carried out in the most beautiful and noble way.)

The world came to Belgium’s aid

The world came to help, causing occupied Belgium to expect yet another useful task from the CRB.

“La Commission for Relief in Belgium avait encore, en Belgique, une autre charge dont les effets étaient utiles au pays.

Lorsqu’on nous fait une faveur, lorsqu’on nous accorde une grâce, ou que nous jouissons d’un bienfait, n’est-il pas d’une âme bien née de montrer à celui qui nous a assistés que nous sommes dignes des égards qu’il a manifestés pour nous? Comment le lui prouver autrement qu’en l’associant jusqu’aux plus petits faits de notre existence.

Le monde nous secourait, il fallait qu’il sut ce que nous faisions de ses secours et la Commission for Relief devait être là pour le dire.”[4]

(“The CRB performed another useful task for Belgium.

When someone grants you a favor, a privilege, or a benefit, it is fitting that you, as a well-mannered person, let the person who gave the support know that you deserve the attention you are receiving.

What better way to show the benefactor that you are worthy than by connecting him with the smallest events of your existence? The world came to our aid, so the people of the world had to know what we were doing with its aid, and the Commission for Relief had to be there to tell them.”)

Reuse of the flour sacks – propaganda

The reuse, transformation and decoration of the flour sacks offered the makers – the schoolgirls, young women and artists – the opportunity to connect the benefactors “with the smallest events in their existence” and to let the world know what the Belgian population had done with the relief. For a second time, the flour sacks were used for charity.

In an organized manner, the makers were able to translate their strong patriotism into heroic images and symbolism. It enabled them to fulfill their charitable duty as well as to conduct patriotic propaganda.[4A] The censorship of the German occupier and the blockade by the British navy led to a strong link of Belgian patriotism with American symbolism. A few individual cases showing Canadian symbolism formed the exception to the rule.

The tribute to America thoroughly exaggerated

The “Tribute to America” on the flour sacks was thus thoroughly exaggerated in February, March 1915. After all, the sacks would all be sent back to the USA to be sold for new food relief.

“American flour sacks.

All over Belgium, ladies and painters are now working hard to decorate hundreds and hundreds of empty flour sacks from the American Relief Fund by needlework or painting. (…) All this is being prepared, (…) to be sent to America as a tribute from the Belgians for the relief provided by America, and it promises to be a worthy tribute, because it will include work by first masters.”[5]

“While all kinds of supplies are coming to us from the billion-dollar country to help the Belgian population in distress and need, our female element has sought and found a way with such fine tact and generous feeling to show the Americans a token of deep gratitude.”[6]

“We are still well supplied with food: America provides everything. Long live America! We receive flour and patent flour every week (…) We now, to show our gratitude to our benefactors, embroider empty flour sacks with three-coloured drawings and the inscription: «Het dankbaar Opwijck aan de Vereenigde Staten» (grateful Opwijck to the United States), and others. (…) This is how they work in all villages and it seems that our work will sell in dollars to the billionaires who want memorials of deeply ravaged Belgium. The proceeds are for us.”[7]

The paradox of gratitude – frugal donations from America

Now the paradox of gratitude, the “Tribute to America” on the flour sacks, comes in.

The promise that the decorated sacks would be sent back and would yield a large return for new relief was not fulfilled.

- The intention to ship the decorated flour sacks to the US, – announced with great enthusiasm – only took place after the Armistice, with the exception of a shipment that was sent to New York in 1915 for propaganda purposes.[8] The sacks raised a minor amount of dollars for the relief work.

- The people of the United States donated only a few percent of the food imports.[9]

The Canadian population contributed more on average per capita.[9A]

“Sadly far from true”

The American CRB representatives have explicitly told the world time and again that the American contributions were frugal.

Laurence Wellington – Province of Luxembourg:

‘Mr. Wellington (…) brought with him many interesting souvenirs of his work in Belgium, including several American flour sacks artistically painted by women and children in that province.

“Americans are the real people in Belgium,” said Mr. Wellington. “They do not seem to be able to sufficiently show their gratitude for what the American people, through the Commission, have done for them. The commonest expression to be heard everywhere by the Americans in Belgium is:- “Sauf par vous, nous serons morts de faim”;- “But for you we would have starved to death.”[10]

Samuel Seward jr.-Province of Limburg:

To the Belgians the relief that has come to them is a very simple thing – the practical expression of your providential, generous sympathy. And their response is as simple and direct. What matter that the complex significance of the Commission escapes them – its wide international scope, its unique diplomatic problems, its efficient engineering methods of administration?

(…) for the average notary in his village, the peasant on his farm, or the nun in her convent, the one great fact is enough, – that actual hunger threatened them- when a great, friendly nation stepped in, in time, to save. (…)

One of my occupations at times of leisure was to say “Thank you” for some of the presents that came pouring into the office- not personal presents, but expressions of gratitude to you in America and elsewhere, friends whom those in Belgium had never seen. The favorite form was to take a flour sack, preferably one that had been specially stamped as gift flour from a certain town or mill, and to ornament it variously, with embroidery, drawn work, painting, in symbols of friendly “reconnaissance.” Sofa pillows were made in this way, table covers, workbags, tea-cosies, little dresses, even, and quaintly shaped caps.’[10A]

Edward Eyre Hunt, province of Antwerp:

‘There was something almost ritualistic in the reiteration of their gratitude.’[11]

Charlotte Kellogg, née Hoffman:

‘Mrs. Kellogg said that there is great gratitude in Belgium towards the United States. “The mass of people in Belgium believe that we are doing everything, even though this is sadly far from true,” she said. “In money the United States has taken care of Belgium about one month of the two and one quarter years of the war.”[12]

Frederic Chatfield, Province of Liège:

‘The country is given credit far beyond its merits. ‘I felt a sense of shame. It seemed as if I were receiving this extraordinary tribute of which I was not worthy. (…) The Belgians give America all the credit for the relief that is saving their lives. The work is carried on by Americans, our stores are known as American stores, $150.000.000 worth of foodstuffs have been purchased in the US and bear the American label.

France and England notwithstanding the heavy expenses of the war are providing the CRB with $10.000.000 a month, more than the US has contributed in nearly two years and a half. Knowing this it is no wonder I felt that I was the unworthy recipient of a great honor.

(…) he presented me with a large bouquet of roses, and this is what he said as he pressed the flowers into my hand: “If we had known that one day these roses would come into the hands of an American, we would have cultivated them with greater care.”

That was the sentiment. It was not for Fred Chatfield that the good wishes, the admiration, the eternal gratitude of this people was expressed, but for an American, typifying the regard of the Belgians for America and all Americans.’[13]

Food shortages and famine

The propaganda for the food supply of occupied Belgium has always been so strong that to this day the reality is hard to face. The preserved tributes on the “American flour sacks/sacs américains” contribute to the continued formation of the myth.

“The idea that (American) philantropy spared Belgian children from going hungry is blatantly untrue.” (Nel de Mûelenaere, 2021). [14a]

In total, the relief for occupied Belgium failed in food aid, local food production and distribution. The import of food covered a maximum of 25% of the needs; in 1915 it helped to control prices; in the years 1916-1918 there were major shortages and famine.[14b]

Has Canada been thanked?

In September 1914, Belgians living in Canada had taken the initiative to collect relief supplies for Belgium via the Œuvre de Secours pour les Victimes de la Guerre en Belgique established in Ottawa and Montreal.[15] The Canadian population, already involved in the war, responded enthusiastically and collected many relief supplies and money. The Canadian ships with relief supplies were among the first to arrive in Rotterdam.

As a result, Emile Francqui, director of the CNSA in Brussels, wrote a letter of thanks to the treasurer of the Œuvre de Secours pour les Victimes de la Guerre en Belgique, H. Prud’homme in Montreal, on 15 December 1914. He addressed Prud’homme as a Belgian and fellow countryman, he thanked him for the goods that were so welcome in “your unfortunate country”:

“C’est à vous que nous devons cet heureux résultat et nous ne pourrons jamais assez dire combien nous vous en sommes reconnaissants et jusqu’à quel point vous avez là servi les intérêts de votre malheureux pays.

(…) avec nos remerciements et ceux de milliers de gens que vous avez ainsi secourus (…)”[16]

(“It is to you that we owe this happy result and we can never express sufficiently how grateful we are to you and to what extent you have served the interests of your unfortunate country. (…) with our thanks and those of thousands of people whom you have thus helped (…)”)

A surprising insight: the Canadian identity of the sacks might also be hidden under USA symbolism, because the Canadian benefactors and/or the organizers of Canadian relief for Belgium were Belgians living overseas…

Table of contents: blogs on the Canadian flour sacks:

Lake of the Woods Milling Company, Keewatin, Kenora, Canada

Canadese bloemzakken met Belgische dank aan het ‘Moederland’

One million bags of flour from Canada to Great Britain

Dank van Puers/Flour Canada’s Gift

Footnotes:

*) Sophie de Schaepdrijver used the expression “gigantisch opgeblazen” (“thoroughly exaggerated”) for the authority of American plenipotentiary minister Brand Whitlock in Belgium. The idea was that American protection contributed to the morale in occupied Belgium.

“Whitlock was attributed greater power than he actually possessed; his title of “ministre protecteur” of the food relief was gigantically blown-up to the “protector of the entire country against the greed and arbitrariness of the occupier”.”

DE SCHAEPDRIJVER, S., De Groote Oorlog. Het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog, 1998, p. 114-115

**)JAUMAIN, S., Un regard original sur la Belgique en guerre. Le Devoir de Montréal (1914-1918). In: Michael Amara et al., Une Guerre total? La Belgique dans la Première Guerre mondiale. Nouvelles tendances de la recherche historique. Bruxelles, 2005 p. 343-365. 5.3. « Un pays dévasté? », p. 357

***) PROCTOR, T.M., “U.S. Food Aid and the Expectation of Gratitude, 1914-1950“, 2011. The validation of American aid to foreign countries became dependent on the gratitude of aid recipients. It determined the relationship between the US and European countries. “American leaders called for assistance for war victims with the understanding and expectation that Europeans would not only understand and welcome the aid, but would also show appropriate gratitude.”

Proctor’s newest book was recently published: PROCTOR, T.M., Saving Europe. First World War Relief and American Identity. Oxford University Press, 2025. She also wrote a blog about the current American foreign aid policy: “The end of the “American Century”?”, Oxford University Press’s Academic Insights for the Thinking World, 16 February 16, 2025.

[1] PICARD, E., Heures de Détresse. L’Œuvre du Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation et de la Commission for Relief in Belgium. Belgique 1914 – 1915. Bruxelles: CNSA, L’ Imprimerie J -E Goossens SA, 1915, p. 17

[1A] PROCTOR, T.M., London & the Making of Herbert Hoover. Blog on the website North American Conference on British Studies, January 17, 2025

[2] Heures de Détresse, p. 20

[3] Lloyd anversois: journal maritime emanant des courtiers de navires, December 25, 1914

[4] Heures de Détresse, p. 21

[4A] DE SCHAEPDRIJVER, S., Shaping the Experience of Military Occupation: Ten Images. In: Rossi-Schrimpf, Inga, Kollwelter, Laura, 14/18 – Rupture or Continuity. Belgian Art around World War I. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2018, p. 43-58.

[5] De Vlaamsche Stem: algemeen Belgisch dagblad, June 12, 1915

[6] De Kempenaar, March 21, 1915

[7] Brief van Celine Geeurickx-Moens in Opwijk, 5 april 1915. Geciteerd in De Belgische Standaard, May 7, 1915

[8] America Feeding Belgian Children, Literary Digest, February 12, 1916.

[9] WILLIAMS, JEFFERSON and MAYFAIR, The Voluntary Aid of America. New York, London: 1918

[9A] PRINCE, B., Le Canada et la solidarité internationale à la Belgique (1914-1921). L’Œuvre de Secours pour les Victimes de la Guerre en Belgique. In: Revue Belge d’Histoire Contemporaine, LIV, 2024, 1-4.

[10] CRB Press Department, New York, August 9, 1915. HILA 22003 box 324 NY Office PR file 1915-1919

[10A] SEWARD, S.S. Jr., Delegate for Limbourg, Belgium, June – Dec 1915. Professor Samuel Swayze Seward (1876-1932) – HILA Seward (Samuel Swayze) papers 1915-1932; collection nr. 40005

[11] HUNT E.E., War Bread. A Personal Narrative of the War and Relief in Belgium. New York: Henry Holt & Company 1916

[12] The San Francisco Examiner, January 21, 1917

[13] Cincinnati, March 21, 1917. HILA, Frederick H. Chatfield papers 53008 Box 2

[14a] DE MÛELENAERE, N., Still Poor, Still Little, Still Hungry? The Diet and Health of Belgian Children after World War I. In J. Nordstrom (Ed), The Provisions of War: Expanding the Boundaries of Food and Conflict, 1840-1990 (pp.207-217) Article 12 (Food and Foodways). The University of Arkansas Press, 2021

[14b] SCHOLLIERS, P., Oorlog en voeding: de invloed van de Eerste Wereldoorlog op het Belgische voedingspatroon, 1890-1940. Tijdschrift voor Sociale Geschiedenis, 11de jg., nr. 1, February 1985;

NATH, GISELLE, Brood willen we hebben! Honger, sociale politiek en protest tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog in België. Antwerpen: Manteau, 2013

[15] PRUD’HOMME, H., Relief Work for the Victims of the War in Belgium. Report on donations received and shipments made to Belgium since the Work was started up to February 5th, 1915. Montréal, February 5th, 1915

[16] FRANCQUI, E., Letter to H. Prud’homme, Montreal, December 15, 1915. Carbon copy letter in the Belgian State Archives, Brussels.