Online I discovered a remarkable portrait of German soldier Ludwig Jacobi, painted on a flour sack in 1916.

I’ve come across another flour sack which was in German possession; a beautifully painted Sperry Flour – American Indian flour sack has been in the collection of German physician Leo Jacobsohn.

What do I know about the German occupiers in Belgium and the Belgian relief flour sacks?

I am collating it in this blog.

1) Ludwig Jacobi, soldier, portrait on flour sack [1]

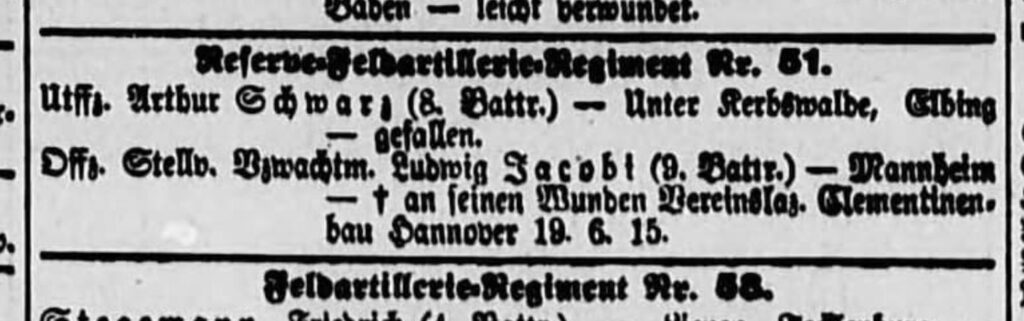

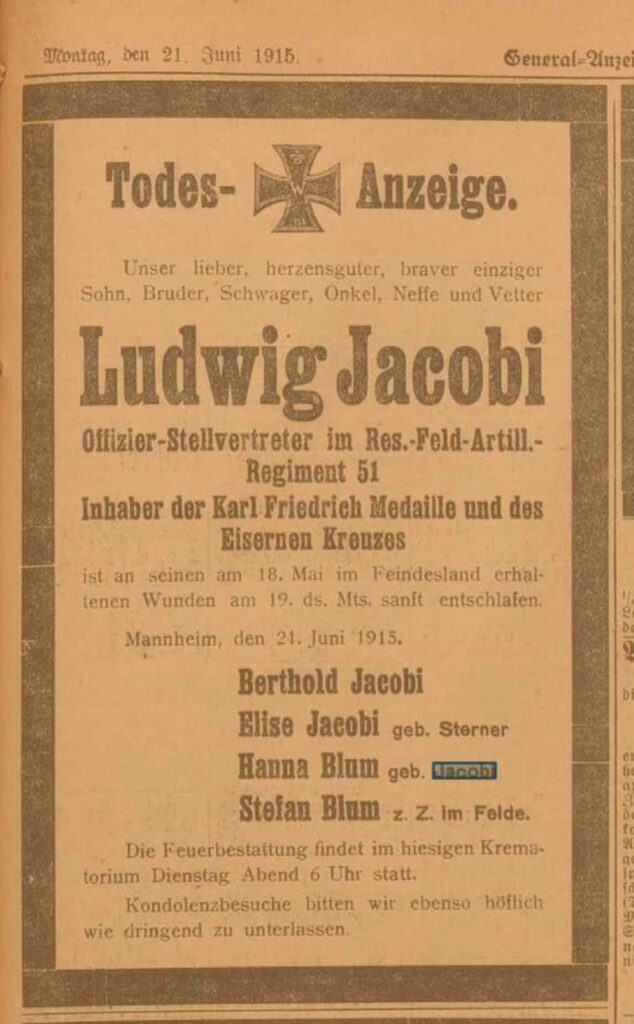

An artist painted the portrait of the German soldier Ludwig Jacobi on flour sack in 1916. On the back is written: ‘Offr.-Stellv. gef. June 19, 1915, Res. Feldart. Reg. 51’. It is an oil painting; dimensions 36×29 inches (91×74 cm). The portrait is preserved in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives (HILA) collection. I have no further information. Is it a flour sack? A German one? Could it be a Belgian relief flour sack?

Until now I have seen portraits of dignitaries painted on Belgian relief flour sacks: a few Belgians, namely King Albert, Queen Elisabeth and Minister of State Emile Vandervelde, as well as the American Minister Brand Whitlock. These are portraits painted from photographs. Artists also painted using models, with women and children modeling.

But here on a flour sack the portrait of an ordinary person whose identity is to be established. And again, a German soldier!?!

Addition Kris Vandenbussche via Lizerne Trench Art Facebook group:

“Vize-Wachtmeister” Ludwig Jacobi (°Mannheim, Germany, 1883-03-23) was appointed “Offizier-Stellvertreter” (a non-commissioned officer could, in the absence of officers, perform the function of Officer) in the 9th battery of the “Reserve Feldartillerie Regiment 51”. This unit was in 1915 in Belgium around Ypres (Poelkapelle, Langemark, St-Julien).

After being wounded near Ypres, Belgium, Ludwig Jacobi was transferred to the Red Cross Vereinslazarett Clementinenhaus in Hanover, Germany. He died on June 19, 1915.

His grave is located at the Jüdischer Friedhof in Mannheim.

Ludwig was the only son of the cigar manufacturer Berthold Jacobi and Elise Sterner.

Ludwig’s sister, Jeanette Johanna (“Hanna”) Jacobi (°Mannheim, Germany, 1887-04-29 + Santa Clara, Ca., USA, 1962-10-10) married Stefan Blum (°Mannheim 1877-06-11 +1962-11-15), the couple had four children; they emigrated to the US in 1938. In the Landesarchives of Baden-Württemberg there is a file, 10 cm in width about the Wiedergutmachung of expropriations of Jewish families + about the diminished German nationality of emigrated Jews in the name of Jeanette Jacobi (“Hanna”) and Stefan Blum.

About the painting:

it appears to have been painted from a studio photograph, as it is dated after his death.

The uniform bears the insignia of a “vize-Feldwebel” or in his case: a “vize-Wachtmeister”. The sleeve covers are typical for artillery. The grenade on the shoulder pad also indicates a “Feldartillerie” unit. In his buttonhole we see two ribbons: the upper one for the Iron Cross 2nd class; below that of the “Badische Silberne Verdienstmedaille des Militär Karl Friedrich”.

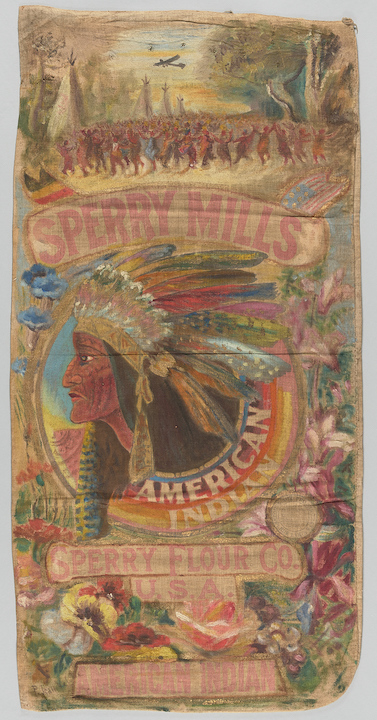

2) Dr. Leo Jacobsohn, doctor, flour sack painted by P. Jean Velghe [2]

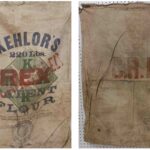

The origin of the painted flour sack of Dr. Leo Jacobsohn is the miller “Sperry Mills American Indian – California”, the sack bears the stamp “Secours au Prisonniers, Rue Lamir, Mons”. [3] An intriguing painting. A crowd of happy people (Native Americans?) are dancing around in an open field, tipis sticking out above the crowd, an airplane in the sky. A Belgian and American flag is waving above exuberant flower garlands with cornflowers, poppies and violets. The feathers on the Native American’s head have been colorfully painted.

It is difficult to read the painter’s signature, but Hubert Bovens, Belgian specialist in researching artists’ biographical data, has succeeded in deciphering the name: P. Jean Velghe. Who was he?

One possibility is: Pierre Jean Aimé Velghe (°Neuilly-sur-Seine 1889-03-22 +Paris (9e Arr.) 1939-11-10). Velghe was an antiquarian, two uncles were painters. He was married to Louis Benoite Antoinette Camous.

P. Jean Velghe’s name does not appear in databases of Belgian artists. Online we believe to have found one other painting by him: Echarpe de la Reine, 1929.

Dr. Leo Jacobsohn (°Putzig, Germany, 1881-05-21) obtained his doctor’s degree from the University of Freiburg in 1905. He traveled to New York and Brazil in 1907. From 1914 on he worked in a hospital in Berlin; during World War I he was part of the Berlin Health Commission. Jacobsohn frantically collected printed matter and newspaper clippings. Through connections in higher circles, he had access to printed matter that was not publicly available. Even after the war he continued to expand his collection of posters, leaflets, and newspaper articles. When Hitler came to power in 1933, collecting stagnated. Jacobsohn was Jewish, he left Germany in 1938 and moved to Los Angeles; he worked as a doctor in a hospital and died in 1944.

Where and when did Jacobsohn come into possession of the flour sack? During the German occupation of Belgium, Jacobsohn traveled through Belgium by train; his archive contains train tickets from Charleroi to Brussels and Charleroi to Antwerp between July 27, 1915, and October 25, 1917. He may have bought the painted flour sack at that time. Had he been in contact with American delegates of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB)? Did he meet William Sperry, descendant of the Sperry Mills family?

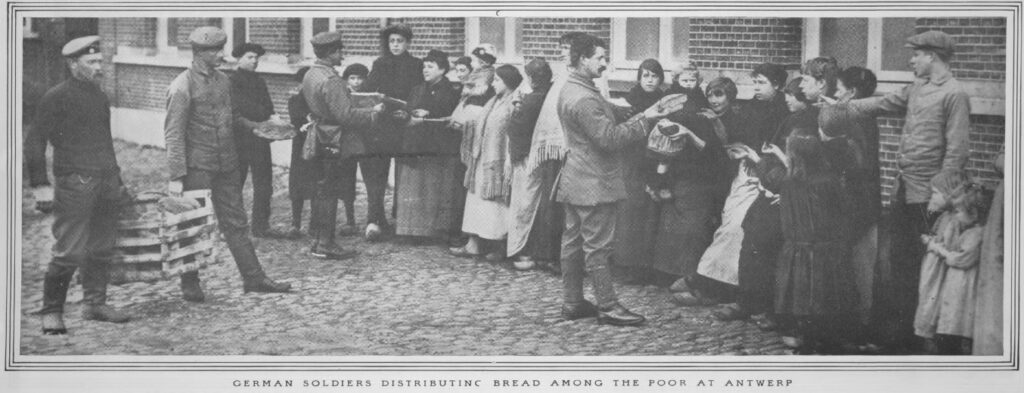

3) German propaganda about food distribution to the Belgian population

Germany worked hard on its image in the neutral countries. The population in occupied Belgium is being supplied with food, was the message in November and December 1914 as conveyed through photos in the authoritative American newspaper New York Times.

The Dutch newspaper Haagsche Courant published a photograph as well.

German regulations and censorship

In spring 1915, the German occupier issued decrees throughout Belgium, which would have influenced the decorations applied to the flour sacks. An example of the Ghent region.

In Ghent, the German commander first made an “Announcement”: the sales and offering of photographs and images of the Belgian royal family in warehouses or on the street was prohibited. Persons preparing printed matter or images ‘which allegedly contained an insult to Germans‘ were threatened with prison and fines (Ghent, April 21, 1915).

Next an Ordinance of the “Etappen-Kommandant” came into effect: the sales and wearing of signs in French, Russian, English and Japanese colors, in particular together with the Belgian colors, was prohibited for the area of the “Etappen-Kommandatur” (Ghent, 25 April 1915).

Three months later the Belgian national holiday was enthusiastically celebrated on July 21. A new Ordinance of the Etappen-Kommandantur followed, which banned: the wearing, display and sales of the Belgian colors, of statues and portraits of the royal family, of green leaves with and without inscription and of all signs and color combinations “which are suitable to display a political inclination” (Ghent, July 23, 1915).

Almost all flour sacks bear patterns and tokens of patriotic symbols. Were most flour sacks decorated before the German bans came into effect? Or did the schoolgirls, young women and artists consider the decoration of the Belgian relief flour sacks an eminently suitable project to willfully ignore the occupier’s prohibitions? Did they feel protected by the local relief committees and the American delegates of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB)?

Flour sack sales and censorship

In my research I have established the intervention of Germans at an Antwerp flour sack exhibition once before.

Allegedly, the Germans did dare to interfere with the flour sacks, despite the protection of committees and the CRB, although I have found only one true example in January 1916 at an exhibition in Antwerp: “… the Germans came on inspection in the halls of the “Harmonie Maatschappij”. They naturally are not liking the fact that the starvation of Belgium under German rule and the protective action of a neutral country are thus made public. They practice “censorship” on the sacks and several copies that they thought were too patriotic were taken away. Including those on which the Antwerp painter Hagge (note: should be Halle*) had depicted King Albert and Queen Elisabeth at the front.” [4]

5) Keep the flour sacks out of the hands of the German occupiers?

Over the years, both in Belgium and the USA, a public perception has emerged that the flour sacks have been decorated because they “should stay out of the hands of the German occupiers”. The story goes that the Germans would like to use the flour sacks for war purposes. To prevent this, the sacks were handed over to Belgian women and had to be transformed into clothing and decorative objects.

The Lace Center in Bruges refers to keeping it out of the hands of the Germans.

At another instance, visiting an exhibition, I read the remark that the Germans wanted to use the cotton flour sacks as sandbags – meaning the use of sacks for military defense.

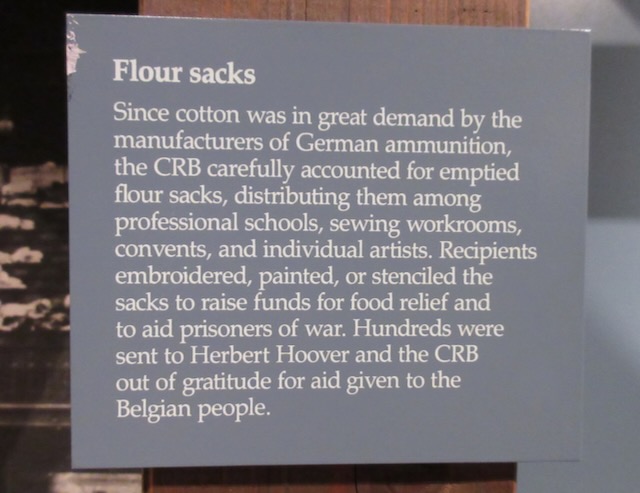

The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library – Museum (HHPLM), West Branch, Iowa, mentions another military use – the intention to use the cotton of the flour sacks for military assault. It states on display boards that the Germans could produce ammunition from the flour sacks: “Since the Germans needed cotton to manufacture ammunition, the Commission for Relief in Belgium carefully monitored who received the flour sacks”.

Looking for resources

For years I have been intrigued by the concept that the Belgian relief flour sacks were decorated because they had to stay out of the hands of the Germans.

Honestly, after five years of intensive research, I have never come across a primary source (a file or document from 1914/1915), mentioning this reason for decorating the flour sacks.

Neither in Belgium nor in the USA have I found any indication that in 1914 and early 1915 – the period when the sacks with Belgian relief flour were sent to Belgium – concerns were raised about how to care for the empty sacks, as they would be of interest to the German army. Nor have I found it as a motive or precaution to therefore hand over the flour sacks to girls’ schools and sewing workshops.

An awkward paradox: how do I refute a belief that presumably has never existed at the time?

Let’s discuss possible sources which may have given rise to the conception of this idea.

Abuse and financial gain in Belgium

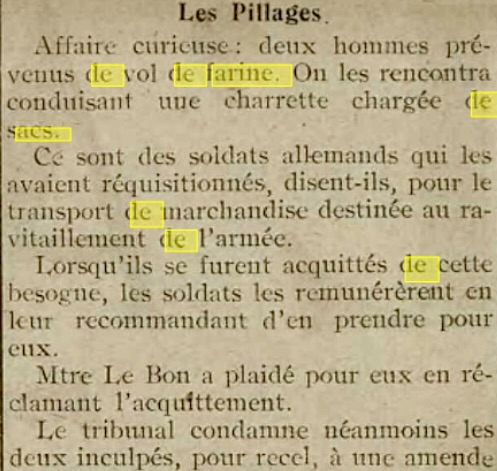

“Loot

Curious case: two men accused of theft of flour. They were detained while driving a cart loaded with sacks. “German soldiers have claimed the sacks,” they declared, “for the transport of goods intended for the supply of the army”. When they had accomplished this task, the soldiers rewarded the two men by encouraging them to take sacks for themselves.”

The judge did not believe their story and convicted them of theft.

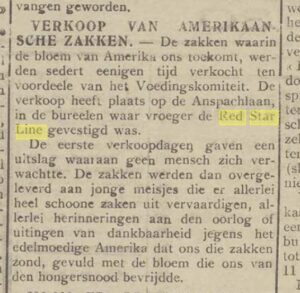

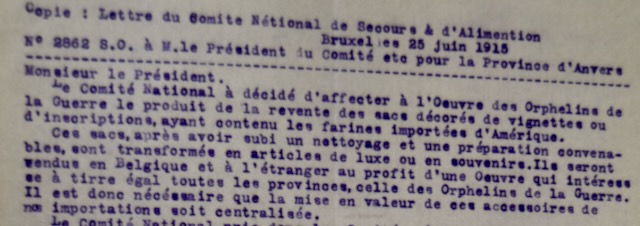

Another primary source on apparent abuse and financial gain of flour sacks is a newspaper article that mentioned the attitude of local bakeries and Belgian individuals. The Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation (CNSA) in Brussels decided that they wanted control over the empty Belgian relief flour sacks. The Committee wanted these to be distributed because the proceeds had to benefit their relief work. [5]

This CNSA decision came late, at the end of May 1915 – to be carried out in June 1915. At that time, decorating the flour sacks had been a craze throughout Belgium for months. Moreover, the provincial committees did not spontaneously cooperate in the desire for centralization. [6]

Would the German military have intended to use the empty Belgian relief flour sacks as sandbags in early 1915? Were the cotton sacks suitable as sandbags in the trenches? Who supplied the regular sandbags for the German military? What specifications did the sandbags have to meet, material strength, dimensions, volume? Under what conditions could the empty Belgian relief flour sacks be reprocessed for use as sandbags? Would the German soldiers have dared to offend the neutral Americans by claiming their empty Belgian relief flour sacks?

I have traced two sources – from after World War II – with stories of two people who played an active, prominent role in Belgian relief in 1914-1918.

Indeed, they both stated that the flour sacks were given for reuse to the Belgian girls and artists, as a precaution because German soldiers had used the empty flour sacks incidentally or were intending to use them as sandbags.

However, are their memories reliable, over thirty years after the war efforts? What would have been the influence of having lived through two subsequent world wars, famines, and German occupations?

An American source – Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover (ºWest Branch, Iowa, 1874-08-10 +New York, NY, 1964-10-20), was director of the Commission for Relief in Belgium from October 1914, based in London In one of his many books he mentioned the reuse of sacks as sandbags by the Germans. It happened in northern France in the third year of the war, 1916. According to the story, the flour sacks – although on a deposit – were resold and used as sandbags. Hoover would then have ordered the empty flour sacks to be sent to clothing workshops in Lille and Brussels. Hoover recalled the event in a book that was published in 1959 [7].

“The British had discovered on captured German trenches sandbags made from C.R.B. flour sacks. The British indignation was only a little less violent than the French when they imagined our condensed milk tins were being used for hand grenades. The French Committee for “benevolence” in the Communes had been making a little money for their charities by selling the empty sacks to dealers who, in turn, sold them to the Germans. After the discovery of this practice, I had stopped it by requiring every maire to deposit 10 francs for each sack to be repaid when the empties were returned. We put the sacks into the clothing workrooms at Lille and Brussels and saw that they were turned into children’s clothes, although the indelible words “Belgian Commission” appeared on many a youngster’s front or back.”

Comments on Hoover’s story

I comment on Hoover’s story based on my research results.

1. Relatively few cotton Belgian relief flour sacks entered occupied Belgium and northern France in 1914-1918. The period of entrance was short, late 1914 to April 1915, and it was only the packaging of the Belgian relief flour that had been collected as charity by the American citizens and mills. The Belgian relief flour sacks were never on deposit; the Americans had intended the sacks to be reused in Belgium. Hence the Belgian “flour sack hype” took place in 1915.

Hoover’s story refers to an event in 1916 in Northern France.

2. The CRB, with a focus on efficiency, bought wheat in bulk, which was transshipped from the ocean steamers into Belgian barges by grain elevators in the port of Rotterdam. In Belgium, the wheat was ground by local mills. The mills used local deposit flour sacks of 100 kg to distribute the flour to the bakers.

3. In December 1915, the CNSA, co-operating with the CRB, introduced a strict system of deposits on all packaging imported by the CRB. This was strictly supervised. [8]

4. The sacks of Belgian relief “charity” flour, in general made of cotton, exceptionally of jute, of 49 LBS and 98 LBS have been recognized as such by the Belgian population and therefore used by them for charity in return.

5. There are no Belgian relief flour sacks with the printing “Belgian Commission”. The sacks were printed with: “Belgian Relief Flour” or “American Commission”.

6. The only “C.R.B. flour sack” I have encountered – once, among the almost thousand WW I flour sacks I have seen – is in the collection of Scott Kraska. Where and when will the red stamp C.R.B. have been put on the back of the flour sack?

It is interesting to read how Hoover played with his neutral American role between the British, French and Belgians on the one hand and the Germans on the other.

A Belgian source – Marthe Boël

Marthe Boël, né de Kerchove de Denterghem (°Ghent 1877-07-03 +Brussels 1956-01-18), prominent Belgian politician for the liberal party and feminist, wrote her undated story “Story of the American Flour Sacks” in a letter which is attached to a decorated flour sack, preserved by HHPLM since 2015.

According to the museum’s data, the flour sack in question was purchased in Belgium after World War II by an American soldier, commander of the “US district”, who had been stationed in Belgium. He took the flour sack and Boël’s story back home. After his death, the flour sack passed to an American family who framed the flour sack and hung it in their daughter’s room. Years later, they donated the flour sack with Boël’s story to the museum. The story is typed on thin sheets of yellow paper, it looks like a carbon copy.

The paper and the story give the impression that Marthe Boël wrote down her story after WWII, in 1945 or later.

Her story is as follows:

“The Germans seeing all that could be done with these sacks even when emptied of their contents had bought through means of third persons and use them as trench sand bags.

….

It was then secretly forbidden to the Belgians to sell the sacks then on the market except for such high prices as would make them prohibitive for the Germans. It was then that people began to decorate and embroider the sacks.

…

These special “painted sacks” were started at the beginning of 1915. It was the moment where it was most important to prevent the Germans from seizing the sacks. People made large hordes of them in their private homes where the Germans could not get at them, buying them up under the pretext of collecting them.

….

Then I was arrested and sent to Germany. The work being started it was continued without me until the moment of America’s entering the war. The Germans then forbade to continue selling or exposing or fabricating objects made out of American flour sacks.”

Comments on Boël’s story

Boël’s memories about the flour sacks understandably bear witness to a strong bias against the German occupier; she wrote down the story about the WWI Belgian relief flour sacks for an American soldier who had fought successfully in WWII for the liberation of Belgium, thirty years later.

For Marthe Boël, the main point was that the enemy had to be thwarted by all means, literally at all costs; according to her, the Belgians were only allowed to sell the sacks at such high prices that they became inaccessible to the Germans. However, this was a secret.

The entire reasoning in Boël’s story is so at odds with my research findings that I repeat: elements are recognizable, but it does not offer a historically reliable document about the German occupier and the Belgian relief flour sacks.

In his blog Subversive Flour Sacks of Thanks, Thomas Schwartz, director of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, discusses Boël’s letter. He describes decorating the flour sacks as proof of “the act of subversion and defiance against German occupation”. [9]

A Belgian primary source – Virginie Loveling

About sandbags in Ghent and the embroidery of flour sacks in Belgian cities

The war diary of Virginie Loveling mentions the sewing of sandbags and the embroidery of flour sacks within a span of nine days.

Virginie Loveling (°Nevele, 1836-05-17 +Ghent, 1923-12-01) was a Belgian poet and novelist. She mentioned in her War Diary [1914-1918] the production of sandbags for the Germans in Ghent. [10] Her notes of May 12, 1915: For “the German army administration”, a manufacturer in Ghent “weaves a kind of linen, which later coated with a certain greenish mixture, forms an impenetrable oilcloth. It serves for sacks filled with sand or cement that are used as shelter in the trenches. There are working women who sew such sacks.”

On May 21, 1915, Loveling reported “the embroidering of the sacks which America graciously sent here filled with flour. All will be returned as a token of gratitude. Not only ladies, but also talented painters and fabric designers selflessly offered their help.”

Loveling does not refer to any German interference.

Cotton in 1914/15 – ammunition?

In newspaper reports, I read about the collapse of the world cotton market. But I also read about American ships with cotton freight for Germany, ships which were brought in by the British navy and later released, enabling the ships to supply German customers with cotton.

On August 21, 1915, Britain declared cotton contraband, ie. raw cotton, cotton linters, cotton waste and cotton yarns. The Netherlands no longer received British raw materials for their Twente cotton industry all of a sudden and noted “Cotton was the most important war material!” [11].

How and when could the German military industry have used empty cotton flour sacks from occupied Belgium in their arms production during WWI? In the production of ammunition? Were the references intended to indicate gun cotton?

An American source – Phyllis Foster Danks

Phyllis Foster Danks, HHPLM curator from 1977 to 1986, did research on the flour sack history in the year 1979. She reportedly discovered this intriguing information: “the Germans could use the cotton for gun wadding”. [12]

Therefore, signs in the museum display at West Branch read: “Because cotton was in high demand from the German munitions manufacturers, the CRB carefully counted all emptied flour sacks.”

I am unaware of the sources on which Danks based her information.

What specifications did this cotton have to meet? Was it possible to upgrade the cotton of the flour sacks to this specification on an industrial scale? Were there no alternatives?

Addition August 2, 2023

I submitted the “cotton-ammunition questions” to the staff of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum and received the following response from them:

“Annelien, This is what our Archivist uncovered. It doesn’t answer your questions definitely but, like you, casts doubt on the existing explanations.”

“While I stated that “guncotton isn’t really cotton,” the standard method of manufacturing guncotton (a form of nitrocellulose) during the Great War period was to expose cotton to a combination of sulfuric and nitric acids. Other starches or wood pulp could be used, however.

Conclusion

In this blog I have assembled what I know about the German occupier and the Belgian relief flour sacks. At issue were:

1) the portrait of the fallen German officer Jacobi has been painted on a flour sack.

2) the Belgian relief flour sack in the collection of German physician Dr. Jacobsohn.

3) the German propaganda about food distribution to the Belgian population.

4) a German ban on images of members of the Belgian royal family, flags, arms and national colors of Belgium and the Allies; censorship on a sales exhibition of flour sacks.

5) the modern conception that the flour sacks were decorated to keep the sacks out of the hands of the Germans, because they could be used for military defense, and worse, for military attack, seems to have no basis in the actual events in 1914/1915.

I wonder if we are no longer able to imagine that in 1914-1918, the starting point for the flour sack decorating was charitable work and the expression of gratitude for humanitarian food relief? Do the decorated flour sacks have to be seen in a military context, do they need the creation of an enemy, to get attention nowadays?

In any case, we have proof that one decorated flour sack fell into the hands of a German!

Thanks to:

– Evelyn McMillan for the discussions on this topic and for pointing out the secondary sources on the flour sacks-sandbags issue.

Evelyn’s flour sack collection contains the English version of the flour sack with the two children in pajamas in front of the open doors: “God bless America”. Marthe Boël described that she asked some necessitous artists to paint the sacks on the condition that the images would express gratitude to the American people.

– Marcus Eckhardt for the information about the flour sack “Béni soit l’Amérique! Brussels 1916” / Belgian Relief Flour, Russell – Miller Milling Co., Minneapolis, Minn., USA. Coll HHPLM 2015.3.1 including Marthe Boël’s explanation.

– Hubert Bovens for deciphering the name of painter P. Jean Velghe, researching the artist’s life and biographical data on artists.

– Jacques Laperre for the correction of the artist name “Hagge” to Halle, Oscar, and his biographical data; also, Gregory Boite, Mu.ZEE Ostend.

– F. Brenders for his research in the FelixArchief, Antwerp.

– Kris Vandenbussche, via Facebook group Lizerne Trench Art, for the information about Ludwig Jacobi and the Jacobi and Blum families.

*) Oscar Halle (°Bärwalde, Pommern (D), 1857-08-19 +1921?). Decided to become an artist at the age of 21. Took drawing classes in Berlin, took courses at Dresden’s Art Academy, left for Antwerp and became a student of the Belgian artist Verlat. From 1885 he participated in exhibitions in Antwerp and Brussels.

Footnotes:

[1] Hoover Institution Library and Archives website: ‘Unframed unsigned portrait on a flour sack Ludwig Jacobi, 1916’, nr. 19001.126, accessed June 10, 2023

[2] The ‘Jacobsohn collection on Germany between the Wars’ is in the archives of the University of Southern California – Special Collections, Los Angeles, Ca., coll. no. 0080.

[3] USC coll. nr. 0080, Box 29, File 1.

P. Jean Velghe lived in Paris. His parents were married in Paris but were both born in Belgium, resp. in Courtrai and Tielt (West Flanders). One of P. Jean Velghe’s two uncles may have been his teacher: Auguste VELGHE (1831-1912), who lived in Paris for a long time.

[4]

– Text posters and wall messages Etappen-Kommandantur Ghent 1915

– L’Indépendance Belge (Edité en Angeleterre), March 4, 1916; De Stem uit België, March 31, 1916 (published in London from 1916 to 1919)

[5] Het Vlaamsche Nieuws, May 29, 1915

[6] Antwerp Provincial Committee, correspondence of June 28, July 7 and 10, 1915. FelixArchief, Antwerp.

[7] Herbert Hoover, An American Epic. The Relief of Belgium and Northern France 1914-1930. Volume I. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1959, p. 316.

[8] Amara, M., Inventaire des archives du Comité national de Secours et d’Alimentation. Rapport général sur le fonctionnement et les opérations du Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation. Deuxième partie. Le Département Alimentation. Tome II: Appendice: Le Service Stock général et Fabrications, 1921. Brussels: The State Archives in Belgium, General State Archives, 2009

[9] Schwartz, Thomas, Subversive Flour Sacks of Thanks. West Branch, Iowa, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum. Blog: Hoover Heads, January 6, 2016

[10] Van Raemsdonck, Bert, Virginie Loveling’s War Diary [1914-1918]. Ghent, KANTL and University Library, electronic version, 2005; diary May 12, 1915, and May 21, 1915.

[11] ‘Proclamation, dated august 20th, 1915, specifying various forms of cotton to be treated as contraband’. (Van Manen, Dr. Charlotte A., De Nederlandsche Overzee Trustmaatschappij. “Middelpunt van het verkeer van onzijdig Nederland met het buitenland tijdens den wereldoorlog 1914-1919” (Center of the relations of neutral Netherlands with foreign countries during World War 1914-1919)).

[12] Florman, Jean C., ‘Out of War, A Legacy of Art‘. Artikel in: Hemingway, Joanne, Hinkhouse, Belle, Out of War. A Legacy of Art. West-Branch, Iowa: The Iowa City Questers Reciprocity Committee, 1995