The modern view of the history of the decorated flour sacks in World War I is that they were transformed and decorated by Belgian girls, young women and artists in gratitude for food relief as gifts to the Americans, in particular hundreds of pieces of “artwork” were given as gifts to American former president Herbert Hoover. [1]

Uncertain if “artworks” were presents for Hoover

My first encounter with an embroidered flour sack immediately called this notion into question. My sensory, tactile experience was part of this process. I saw, felt and smelled a piece of cotton in which flour had been packed, holes had been punched, on which a pattern had been embroidered with various embroidery stitches in different colors -brand names and logos of aid organizations and mills-, a piece of lace had been attached, a ribbon had been threaded through a traditionally made buttonhole; the cotton smelled slightly musty and from time to time flour residue fell out.

The embroidered years “1914 – 1915” marked the early years of the fierce war, battles, roaring cannons, muddy trenches, executions, gas attacks, prisoners of war and refugees. The flags and national colors of Belgium, the USA and Canada showed a deeply felt patriottisme.

Would these flour sacks really have been worthy gifts for the Hoovers who would become President and First Lady of the United States a decade later?

My doubt grew stronger when I studied the collection list of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum (HHPLM), I got an impression of the quality of the work, the choice of sacks from the same origin (American Commission), the repetitions in embroidery and needlework, such as “good night bags”, tea cozies, tablecloths, aprons and book covers. How could the abundance of school projects be explained? Did the Hoovers indeed keep these as souvenirs at home?

The social life of the decorated flour sacks

The meaning I assign to the flour sacks will be different from what the Hoovers assigned to the sacks. In comparison to them I am alive a whole century later; I am of a generation that has not personally experienced war; I grew up in Dutch culture; I did not work – or partner with anyone – in a prominent position in international business and later in national politics; I have not lived outside my country of nationality for many years; I didn’t move or have multiple houses to decorate.

I realize that in 2023 I occupy a different position in history.

The decorated flour sacks of WWI are trench art, they are items made by civilians directly from materials associated in time and place with the consequences of armed conflict.

Decorated flour sacks have a “social life” as objects, we humans come into contact with them, they move with us in time and space. [2]

The Hoovers and the decorated flour sacks

During my American Sack Trip in 2022, I found a number of connections between the Hoovers and the decorated flour sacks. They follow chronologically.

During WWI

1915 – New York

Lou Hoover had interfered in the sale of decorated flour sacks in the US. She received a letter from a friend in New York who suggested selling “the touching flour sacks which could be used for porch pillow covers in the country and for laundry bags and various things” for $1.50 to $2. (1915) [3]

Herbert Hoover wrote a letter to William C. Edgar asking him to order more decorated flour sacks as the Belgian children were still “industriously embroidering” them. [4]

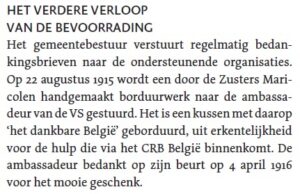

1916 – Antwerp, Belgium

Piet van Engelen’s “Rooster on an oak branch at dawn”, flour sack “A.B.C.” was presented to Herbert Hoover as director of the CRB in July 1916 in Antwerp. [5]

After WWI

1919/1920 – Victor Horta

Lou Hoover was decorating her new home in California. She had written letters to Belgian architect Victor Horta about the furnishing of her Stanford home on the university campus, wanting a separate room designed specifically for Belgian memorabilia with a display rack for decorated flour sacks. [6]

1924 – Brooklyn Scouts

In 1924 Lou Hoover established a connection of the Brooklyn Girl Scouts with the Friends of Belgium who donated a flour sack painted by Paul Jean Martel to the Girl Scouts in gratitude for their contribution to the food relief. A ceremony in New York was held with the Belgian ambassador, but Lou Hoover was not able to attend. [7]

1928 – Oostkamp, Belgium

Lou Hoover received an Oregon journalist at the Hoovers’ home in Washington. The journalist was shown an embroidered flour sack pillow from Portland, Oregon. The newspaper article described that the cushion was inside a dark, carved wooden box. On the pillow rested a Belgian acknowledgment written on parchment. The Belgian souvenirs were in Herbert Hoover’s study. [8]

During my research at the Hoover Institution Library & Archives (HILA), I photographed the pillow. The embroidered acknowledgment reads: “’t Dankbare Oostcamp aan hunne geliefde Weldoeners van Amerika.” ([From] The Grateful Oostcamp to their beloved Benefactors of America.) *)

It is a satin pillow embroidered with silk threads. The bottom is finished with a cotton flour sack of Oregon origin. The brand name is Cascadia from Portland Milling Co., Portland, Oregon.

The silk cushion was embroidered by the Sisters Maricolen on behalf of the Oostkamp municipal council, which paid 300 francs for the piece. The cushion was gifted to Mr. Brand Whitlock, American minister plenipotentiary in Belgium!

Apparently, the pillow later ended up in the Hoover household and was combined with the gilden, carved box and the parchment. [9]

The beautiful Belgian souvenir from Oostkamp, given as a gift to America, has led a life of its own over the past hundred years. It is a showpiece that likes to be displayed. On TV footage, the pillow and gilded box were shown by Dare Stark McMullin, Hoover’s secretary. [9c]

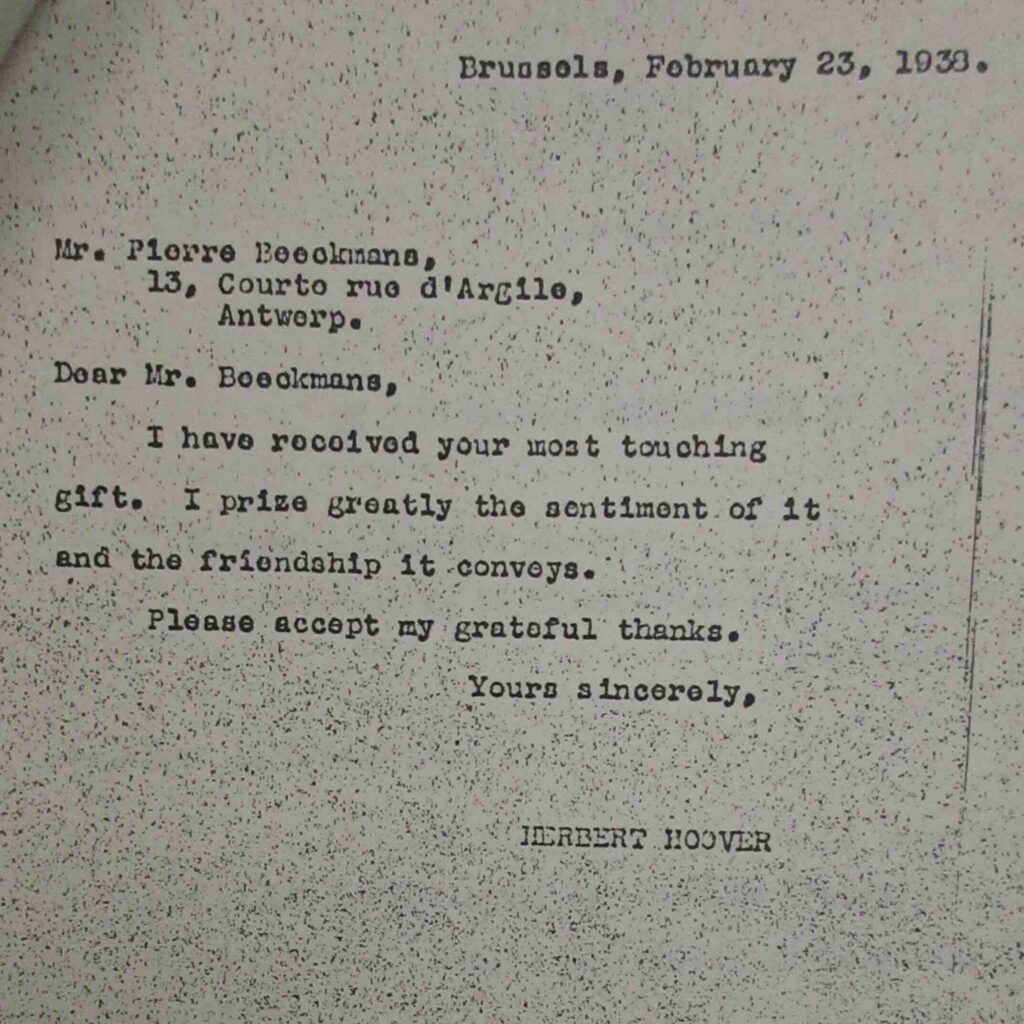

1938 – Pierre Beeckmans, Antwerp, Belgium

In 1938, Herbert Hoover travelled to Brussels and received a painted Chicago Evening Post flour sack as a gift from Pierre (Petrus) Beeckmans, Antwerp. Beeckmans writes in his covering letter to Hoover dated February 22, 1938, that the flour sack “remembers excellently the remarkable philanthropic work you accomplished during the tragical years of the Belgian people”. [10]

In his letter, Beekmans refers to the year 1915 and to the original flour sack which had been in his family since that year. But still, there is something very strange about this flour sack.

I think is likely that the painting and a stamp of the “Orphans of the War” were only designed and applied in 1937/38 at Beeckmans’s request.

First, the flour sack was not painted in 1915 but is certainly painted after the Armistice as the years 1914-1918 are depicted.

Secondly the painting of the nine Belgian provincial flags is suggestive. The Belgian flag is missing; during the war years, the flag and/or the colors black, yellow, and red were always part of the decorated sacks’ iconography.

In third place a stamp on the reverse side of the sack mentions the “Orphans of the War”. The stamp’s design, the drawing and the font, is modern and businesslike, with a distinguished appearance. During the war years of 1914-1918, such a stamp did not appear on any flour sack.

Beekmans donated the painted flour sack to Mr. Hoover on his own behalf, not at the behest of the Antwerp authorities. Beeckmans had an “Agency that prepares and carries out all publicity” and likely sought attention for himself and his work in 1938.

Beeckmans responsible for the Persecution of Jews in WWII

Pierre (Petrus) Beeckmans (born in Gooik, Belgium, on August 10, 1894) was a front-line soldier in WWI and got wounded. He rose through the ranks of reserve cadre to lieutenant in the infantry and, after the war, served in the Belgian occupation forces in Germany.

Pierre Beeckmans was an outspoken, far-right Belgian nationalist and anti-Jewish. During WWII, he worked for the Anti-Jewish Central for Flanders and Wallonia, which he led from 1943. Upon liberation, Beeckmans fled to Germany but was arrested in May 1945. During the Volksverwering (People’s Defense) trial, he was sentenced to death; the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1952; he was released in April 1960, at the age of 75. [10a]

1938 – Brussels, Alice Gugenheim

A postcard has been preserved addressed to Monsieur le Président Hoover, Ambassade d’Amérique, rue de la Science 38, Bruxelles, sender Madame Raphaël Gugenheim, in which she asks him if he has received an embroidered flour sack “en symbole de temps de guerre et de la reconnaissance présente et durable.” (as a symbol of wartime and present and enduring recognition.) [11]

1941 – Stanford University

On the occasion of the opening of Hoover Tower at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Ca., in June 1941, Herbert Hoover visited the Hoover Institution’s Flour Sack Exhibit. [12]

60’s (?) – New York

The embroidered flour sack “Comet” by Globe Mills, Los Angeles, California, graced the couch in Mr. Hoover’s apartment at the Waldorf Astoria, New York.[13]

Conclusion as follows from this chronology:

The Hoovers came into contact with the decorated flour sacks and the objects moved with them in time and space.

During the war, both Lou and Herbert Hoover helped to distribute the decorated flour sacks; Herbert Hoover was gifted one decorated flour sack.

After the war, Lou Hoover decorated her home with Belgian memorabilia, consciously showing it to her guests; she helped distribute remaining sacks from the CRB archive.

Herbert Hoover has received decorated flour sacks from Belgian admirers. He once visited an exhibition of the decorated flour sacks in the basement of Hoover Tower.

What did the war memorabilia mean to the Hoovers, what did the flour sacks remind them of?

The Hoovers during the War

The Hoovers, both 40 years old in 1914, were a prominent couple in the international business world. Herbert Hoover was born in Iowa but grew up in Oregon. Lou Henry Hoover was born in Iowa and grew up in California. They were both Stanford mining engineers, he led major global mining projects for raw materials and minerals for industry, she was his sounding board and he hers, they were a team. She created the conditions that made it possible for them to live and work, her task consisted of the home(s), the social networks, the schooling of their two sons. Their wealth was considerable; the Hoovers had the American nationality, but from 1899 they had been living and working outside the American continent, they had settled in London. Their network mainly consisted of American (mining) engineers, who just like them were both internationally active and established.

When Herbert Hoover was asked in October 1914 by the American ambassador Page to dedicate himself from London as director of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) to the supply of food to occupied Belgium, he agreed.

At the time Lou Henry Hoover was with their two sons Herbert Jr, age 11, and Allan, age 7, in California; she had brought the sons to safety from the dangers of the war in Europe. [14]

In California, Lou Henry Hoover worked tirelessly to get relief work for the population of occupied Belgium and the Belgian refugees.

Lou intended to stay in California with her sons. Herbert wanted his wife as a teammate next to him in London: “want you here mightily”. [15]

Lou gave in. She reluctantly left their sons in the hands of family and friends. Aware of the danger of war, she wrote farewell letters to her children in New York in case she would not survive the ocean crossing to the UK. [16] She departed New York on November 25, 1914.

Lou Hoover traveled back to America

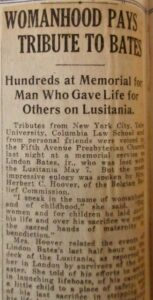

Six months later Lou Hoover traveled back to New York in early June 1915. An unimaginable event had happened.

Their dear friend Lindon W. Bates Jr., son of Lindon W. Bates, Vice President of the CRB in New York, and Josephine White Bates, President of the CRB’s Woman’s Section, had not survived the Lusitania ship disaster. The German submarine U-Boat 20 had attacked the British passenger ship with torpedoes. Lindon Bates Jr. helped rescue his fellow passengers to the end but did not survive himself. Weeks later his body was found on the coast of Ireland. Bates Jr. was on his way to the Hoovers in London to receive instructions about the CRB work he was to undertake in Europe.

Lou Hoover gave an impressive speech at the memorial service in New York in which she said, among other things:

“I speak in the name of womanhood and of childhood (…) For woman and for children he laid down his life and over his sacrifice we reach the sacred hands of maternity in benediction. He remained until the end, helping and comforting. Only as the ship gave her final plunge did he dive, but the suction had become too great for mortal combat.” [17]

Lou Hoover traveled on to California and reunited with her sons; from then on, she would not leave the boys alone during the war.

1919 – After the war – Belgian possessions

Lou Hoover was not the woman to refer to the personal war memories described above in relation to the flour sacks.

In December 1919, a year after the war Lou Hoover was focused on the design and furnishing of her new Stanford home: “the grouping and arrangement of various Belgian possessions.” She asked Belgian architect Victor Horta for advice and wrote him a letter. [18]

“I have many pieces of the most beautiful Belgian lace of the war period, many of them being of large table size. (…) On the other wall or at some point a panel might open to show a loop recess in which were many thin hinged panels, like those in art exhibitions mentioned, on which hung a selection of the quaint embroidered flour sacks presented by the Belgian girls.”

In her description of a painting by Baer of a Belgian peasant girl I read – mutatis mutandis – the significance of Belgian lace and embroidered flour sacks and the memories they evoke for her.

“For instance, there is a very wonderful thing of a peasant girl done by Baer. (…) There is really nothing to describe but the repressed sadness of her face with its downcast eyes and the unutterable pathos of her peasant hand crushing a tear stained handkerchief. (…) we see her with the indefinite background of a ruined village.”

She continued: “But in those old days of before 1918, we used to say she was simply Belgium, sturdy in her sorrow, and even though with unutterable sadness in her heart, ready to look up and meet the problems before her when a turn of fate should come.”

Four months later Lou wrote again to Victor Horta. [19]

“Of course we have such happy memories of Belgium, although we saw her at her saddest. She was so wonderfully brave and marvelously in every way, that we could not be but lost in admiration for her and her people.”

Lou Hoover desired a Flemish interior for war memories

In the continuation of her letter to Victor Horta an illustration can be seen of Lou Hoover’s attachment and preference to making and including physical memories of Belgium during the war.

For her new house she preferred to furnish a room completely in Belgian style. The best way to accomplish this would be to acquire old Flemish wood-carved panelling from one or more destroyed houses and ship it to California.

“And of course, we have some very lovely Belgian things which have been given my husband as souvenirs of war days. My idea was to gather these all together in one room, and to have it decorated in purely Belgian style.

I could think of nothing better than some old Flemish panelling and carving. To me that would be lovely.

Would it be possible to find a room of appropriate decoration, which would be for sale? There must be a goodly number of old houses partly demolished by the war, where owners will wish to sell what is left, – and of them some one ought to be of suitable size and type for possible readjustment.”

She added in her letter that it would have to fit within her budget.

Conclusion

The story of the Hoovers and the decorated flour sacks shows that for them the flour sacks were symbols of gratitude, souvenirs of the war and occupation of Belgium. In view of Hoover’s presidency, the decorated flour sacks even became status symbols of humanitarian aid.

But bringing together the social lives of the sacks and the Hoovers in words and images adds another dimension. The Belgian possessions, including a few decorated flour sacks belonging to the Hoovers were, above all, artifacts that embodied their intense, human experiences during and after the war.

NB. The hundreds of pieces of “artwork” were not a gift to the American president-to-be, Herbert Hoover. Thousands of thanks, including decorated flour sacks, were sent from Belgium and gifted to “the American people”.

*) Read my article in the Oostkamp Historical Society’s Newsletter:

Van Kempen, Annelien, Een Oostkamps borduurwerk gekoesterd door Amerika’s first lady (An Oostkamp embroidery cherished by America’s first lady). Oostkamp, Nieuwsbrief Heemkring Oostkamp, jrg 24, nr. 1, september 2023

Thanks

– Thanks to Matt Schaeffer, archivist of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, West Branch, Iowa. Matt wrote the Hoover Head “What You Learn After You Know it all is What Matters”, after we visited the exhibition at the museum together on June 22, 2022. He then extracted Lou Henry Hoover’s letters to Victor Horta, 1919/1920 from the archives. He realized after all these years that Lou Hoover definitely didn’t prioritize the decorated flour sacks in the decorative decor of her Stanford home.

– Thanks to Hubert Bovens in Wilsele, Belgium, for his searches of biographical data.

– Thanks to Wim Deneweth, author of the book “Oostkamp en Hertsberge in de Eerste Wereldoorlog, Heemkring Oostkamp, 2017”, (Oostkamp and Hertsberge in the First World War, Historical Society Oostkamp, 2017), for his information about the embroidered, silk pillow/flour sack ‘Cascadia’, Portland, Oregon, of the municipality of Oostkamp.

Footnotes

[1] Montgomery, Marian Ann J., Cotton & Thrift. Feed Sacks and the Fabric of American Households. Lubbock, Texas: Museum of Texas Tech University, Texas Tech University Press, 2019.

[2] Saunders, Nicholas J., Culture, conflict and materiality: the social lives of Great War objects.

[3] HHPLM 31-Ihh-sub-b082-08 Belgian Flour Sacks undated letter to Lou Henry Hoover from New York (appr. 1915).

[4] Letter Herbert Hoover, CRB London, to William C. Edgar, Northwestern Miller, Minneapolis, Minn. December 13, 1915. HHPLM curator files.

[5] HHPLM 62.4.447. L’Indépendance Belge, parut en Angleterre, August 22, 1916.

[6] Letters from Lou Henry Hoover, Palo Alto, Ca. to Victor Horta, Brussels, Belgium, December 13, 1919, and April 30, 1920. HHPLM Lou Hoover Subject File box 145 Stanford house 1920.

[7] The Friends of Belgium: Whether the Brooklyn Girl Scouts still own the flour sack, painted by Paul Jean Martel, I have not been able to find out.

[8] Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon) April 22, 1928. Lou Henry Hoover was in Washington, wanting to avoid journalist’s questions about her husband’s candidacy for president, so she suggested checking out Herbert Hoover’s study and “Belgium’s unique gift” but left this to an assisting friend.

[9]

9a) HILA 62008 box 20.1.

Oostcamp (now: Oostkamp) is located in the province of West Flanders, south of Bruges. Wim Deneweth of the Historical Society Oostkamp provided information on the embroidered silk pillow. The chronicle of Georges Claeys “Oostkamp onder de oorlog (Oostkamp under the war) 1914-1918”, (early 1970s, own limited edition, stencilled) is stating that the pillow was embroidered by the Sisters Maricolen, commissioned by the municipal council. The Sisters asked for a contribution of 300 francs, which the city council approved.

(Today the Sisters Maricolen live with 18 sisters in four communities in Bruges and the surrounding area.)

9b) The handwritten note “Document, on parchment in gilt wood box with embroidered satin pillow. Flour sack back – Oregon- embroidery Oostcamp. Handmade by City of Antwerp.”) is on a document in the HHPLM-curator files.

It is the photocopied statement to grant Herbert Hoover, director of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, “le droit de cite” (the city rights) by Mayor and Aldermen of the City of Antwerp, according to a decree of November 18, 1918. (Letter written on parchment from the Mayor and Aldermen of Antwerp, December 5, 1918.)

The HILA staff sent me a photo of the gilded box. This turned out to be a gift from the City of Antwerp to Herbert Hoover, director of the Commission for Relief in Belgium.

Note: the pillow/flour sack (HILA 62008 box 20.1), the gilded wood-carved box and the parchment are in HILA’s collections.

9c) Dare Stark McMullin (1896-1974). Dare Stark McMullin papers, HILA, Palo Alto, Ca.

[10] HHPLM 65.27.13. Pierre Beeckmans, Antwerp, letter February 22, 1938. HHPLM curator files.

[10a] Saerens, Lieven, HET ARCHIEF PIERRE BEECKMANS, een nieuw licht op de Joodse gemaanschap en de Jodenvervolging in België. (THE PIERRE BEECKMANS ARCHIVES, a new light on the Jewish community and the persecution of Jews in Belgium). SOMA Berichtenblad 40 – June 2007, p. 26-31.

[11] HILA Gugenheim (Alice Aron) Papers coll. nr. 61012.

HHPLM 31-1919-66. Postcard Madame Raphaël Gugenheim, Brussels, to Monsieur le Président Hoover, 1938.

In 1938 the Embassy of the United States of America in Brussels was located Rue de la Science 33 (instead of 38).

Alice Aaron (°Toul, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Lorraine, F. 1872-02-29 +Paris 1955-03-25) married Raphaël Gugenheim (ºKolbsheim, Bas Rhin, Alsace, F. 1863-03-09 +1946) in Toul, France, March 1893. From 1938 they lived rue Antoine Bréart 135, Brussels.

[12] Photo HHPLM 1941-68A [Allan Hoover 1980]

[13] HHPLM 65.2.3. Foto Drucker – Hilbert Co., Inc. New York, 4393#10. HILA Herbert Hoover Subject Collection 62008 envelope BBB.

[14] Durlap, Annette B., A Woman of Adventure. The Life and Times of First Lady Lou Henry Hoover’. Potomac Books, 2022, p.74.

[15] Telegram Herbert Hoover to Lou Hoover, November 18, 1914. HHPLM Lou Henry Hoover Papers, box 082.

[16] Durlap, p. 76.

[17] Lou Henry Hoover: “Womanhood pays tribute to Bates”, speech at the memorial service for Lindon W. Bates jr. in New York on the evening of June 10, 1915, New York Tribune, 1915-06-11. HHPLM: BAEF: CRB London Office News Cuttings, 1915 May-August (Box 24).

[18] Lou Henry Hoover to Victor Horta, December 13, 1919. HHPLM Lou Hoover Subject File box 145 Stanford house 1920.

[19] Lou Henry Hoover to Victor Horta, April 30, 1920. HHPLM Lou Hoover Subject File box 145 Stanford house 1920.

I am unaware if any of Lou Henry Hoover’s plans were actually realized.